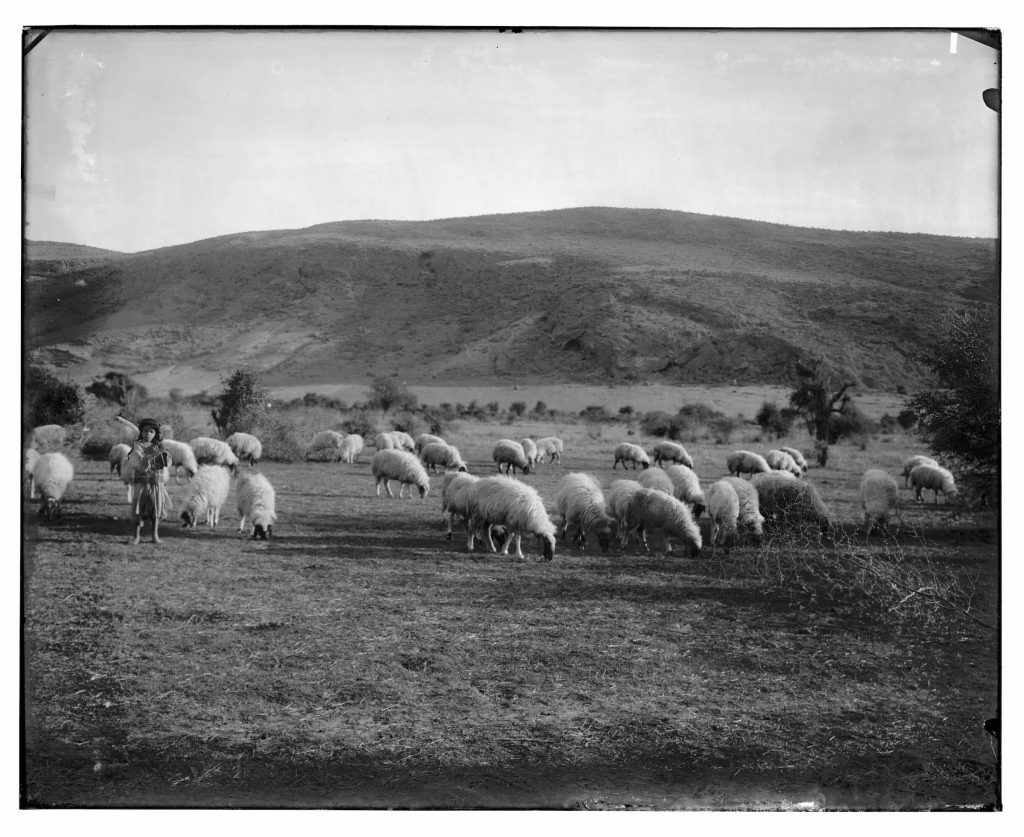

A girls’ school group affiliated with the Arab Ladies Union in the Musrara neighborhood of Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine. Courtesy of the Palestine Museum US.

by: Kaleem Hawa

THE GANGS of Israeli teenagers grip their oversized machine guns as they patrol the Damascus Gate, tossing their stun grenades and hearing the stones roar back in the original Arabic: “Jerusalem for the Palestinians.” What scenes those steps have borne witness to—a Nakba, a catastrophe. A shattering of history, a rending of Palestinian masses, now reunited and marching steadfastly along Route 1 toward Al-Aqsa Mosque on one of the last evenings of Ramadan to protect their city, to defend it from Israeli attempts to cleanse it of Palestinian life. In Jerusalem, a boy throws his shoe at a soldier, hitting him squarely in the face. In the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, the breakers of the fast are pelted by settler stones, summarily returned—and then some. The apartheid state blankets the Palestinians with water cannons, with beatings, with tear gas, and the apartheid newspapers call for peace-on-both-sides, and a deputy mayor of the apartheid city looks on, all bravado, laughing at the injured Native, pointing at his own forehead and saying of the bullet, “It’s a pity it didn’t go here.”

In Jaffa, Akka, and elsewhere, Israeli mobs, enabled by the state police, have begun assaulting Palestinians; in Haifa, they marked the doors of Palestinian homes. In a suburb of Tel Aviv, they attempted to lynch a man presumed to be Arab on live television. In Haifa, Tabariya, and Lydda—sites of an infamous death march carried out by Zionist militias in 1948—Israelis are chanting “death to Arabs.” They are attacking Palestinian stores, homes, and places of worship. In the West Bank, the IDF is deploying live ammunition in response to coordinated demonstrations. Bombs are raining down on Gaza, flattening residential buildings, killing more than 100, lighting up their beautiful sky. A caged people has the right to resist this brutality, however they choose.

On the eve of the Third Intifada, it is clear what got us here: an ideology of Jewish supremacy pervading the entirety of Israeli society. Last month, Bezalel Smotrich—a Knesset member and leader of the ultranationalist Religious Zionist Party—distilled this ideology in his remarks that all Arabs who refuse to recognize “that the Land of Israel belongs to the Jewish People . . . will not remain here.” Though this pronouncement prompted handwringing among some Israelis, Smotrich’s words simply represent the fundament of their state: one established on mass Palestinian depopulations that continue to this day. Journalist and historian Moshe Dann was quick to exonerate Smotrich in The Jerusalem Post, interpreting his words not as a threat of ethnic cleansing but as a purportedly reasonable inquiry into whether Palestinian citizens of Israel can manage to live in a Jewish state. Smotrich’s core question, he writes, boils down to: “Is reconciliation . . . possible, and if so, how?” This deliberate, strategic reframing usefully highlights two common Israeli responses to Palestinian demands for liberation: One engages in or encourages direct physical violence, while another launders the bloodied shirts by calling for “peace,” “coexistence,” and “reconciliation.” In another editorial on Wednesday, as Israel threatened a ground invasion of Gaza, the Post wrote that “what the country remembers most of the violent events of May 2021” may be “the damage caused to the sensitive balance of Jewish-Arab coexistence.”

“Reconciliation” in these formulations is not a politically neutral call for peace, but rather an ideological paradigm predicated on Palestinian submission. The framework purports to provide a path to new relationships between divided groups, redressing historical injustices and paving the way for ethical coexistence. But in Israel, the term is weaponized to coerce Palestinians into passivity in the face of colonial subjugation by implicitly threatening them with state-sanctioned collective punishment—there will be peace on the colonizer’s terms, or else.

This is done with the explicit support and encouragement of the international community. As Palestinian scholar Yara Hawari has detailed in a brief for Al-Shabaka, The Palestinian Policy Network, the reconciliation industry grew out of the 1993 Oslo Accords, when international donors poured millions of dollars into “people-to-people” diplomacy programs, which claimed to help heal bitter divides between parties in conflict. Some of the vanguard advocates of “reconciliation” are groups like the Parents Circle-Families Forum or Seeds of Peace, which aim to bring together Israelis and Palestinians to encourage “musalaha,” or mutual forgiveness. A recent book on the paradigm, Recognition as Key for Reconciliation, describes the core of the agenda as “transformative recognition,” which essentially means: “You forgive us and we forgive you.” The vision here is often one of shared sacrifice, in which histories of injury are set aside so that something “new” can be born. This framing ultimately transforms what should be a project of communal atonement for ongoing harm into an injunction on the individual Palestinian to move on. In placing the responsibility for peace and quiet on the oppressed party, the “reconciliation” framework reveals just how distinterested it is in actually remedying the world-destroying violence being waged against Palestinian life.

In effect, these calls for peace require Palestinians to relinquish their demands for justice. A few months ago, the US Congress voted to pass the Nita M. Lowey Middle East Partnership for Peace Act, a $250 million project that aims to bring together Palestinians and Israelis and reinvigorate a stagnant peace process. In this effort, as in many advanced under the banner of “reconciliation,” there is a knife hidden behind the back; the legislation was passed as part of an appropriations bill that rendered the Palestinian Authority ineligible to receive payments from an economic support fund should they pursue an International Criminal Court investigation into Israeli war crimes. In a ruling on Sheikh Jarrah, where settlers have been trying to expel Palestinians, the Israeli courts generously proposed deferring the violent dispossession by asking the Palestinians to pay rent to those who have stolen their homes.

Contemporary South African history illustrates the way demands for “peace” and “reconciliation” can metastasize. Despite South Africa’s position in the popular liberal imagination as a success story for truth and reconciliation, the nation has failed to deliver meaningful restorative justice to the victims of its apartheid regime. Even while acknowledging apartheid as a “crime against humanity,” the Truth and Reconciliation Commission individualized its victims, rather than defining the apartheid relationship as existing between the state and whole communities. As a result, the process allowed for some interpersonal healing without ensuring broad material programs for the collective Black humanity victimized by apartheid. Meanwhile, reconciliation prioritized shielding apartheid’s beneficiaries: The constitutional negotiations of the early- and mid-1990s resulted in protections for white and Afrikaner property rights and granted conditional amnesty to the perpetrators of violence and terror against Black South Africans. This affective reconciliation, then, doubled as a means of legitimizing the injustices of a new “neoliberal apartheid,” in which the racialized power structures have been preserved, economically and politically.

In Palestine, the insistence on “reconciliation” while Israel continues to ethnically cleanse the Palestinian people amounts to an insistence on surrender. After all, Palestinians’ first ask has always been: stop. Peace and reconciliation before justice and liberation is submission. But this is precisely why the terms remain so attractive to colonizers and their supporters: They allow crimes to continue unabated while diminishing any emotional anguish felt by the culprits. This is always preferable to confronting the soul wound at the core of the Zionist enterprise, which will only be healed by concerted material programs of reparations and decolonization that return Palestinian lands, homes, and dignity.

Approaching that possibility will require a reckoning with the reality of Israel: The Zionist project is a genocidal one. This is not a term I invoke lightly; the violent expulsion and disposession that began in 1948, and the ongoing attempts to disarticulate and destroy an indigenous people meet the definition of genocide from the perspective of international human rights law. Palestinians have long asked the world to understand the recurring Nakba—the Palestinian catastrophe—in this way. After a full and true accounting of all that has been and is being taken from us, the Nakba will demand its justice: End the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people and give it all back.

NEARLY 75 YEARS after the Nakba began, many remain unfamiliar with the full extent of its horrors. In 1996, around 500 pages of International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) documents on the 1948 war in Palestine became accessible to the public. The files—which comprised field accounts and correspondence with local authorities—included details about the detentions of prisoners of war in Palestine and documented violations of the 1929 Geneva Conventions. They detailed the little-known existence of four “official” Israeli concentration camps for Palestinian prisoners; further research has revealed the existence of at least 17 others.

These concentration camps were designed to corral a Palestinian population as Zionist groups like the Irgun and Haganah were stripping them of their land and property. More than 80% of the nearly 6,000 people interned in the “official” camps were civilians. The majority of the detainees were farmers taken prisoner after their villages had been forcibly cleansed; the prisoner population included children as young as ten. Conditions at the camps were harrowing: forced labor, physical and psychological torture, food deprivation, and executions.

When scholars Salman Abu Sitta and Terry Rempel discovered these reports in 1999, they set out to verify the findings of the ICRC, whose visits to the camps had to be pre-arranged with Zionist authorities. They analyzed in-person interviews with 21 Palestinian civilians who had been interned in the camps; these survivors added their personal accounts. Ibrahim ‘Abd al-Qadir Abu Sayf, a villager taken captive in 1949, recalled:

The room [had] a sandy floor to absorb blood and pus. We were tortured; many had broken teeth, hands and legs. Food consisted of one loaf for every fifteen people and one piece of vegetable floating in a big pot. In the early morning we were taken to work. They hit us on our heads to move. If one fell, they hit him with their boots . . . Torture sometimes continued at night. More people came. They were picked up like us, in pastures or in lonely places.

Another former prisoner, Marwan ‘Iqab al-Yahya, said: “[We were] lined up and ordered to strip naked as a punishment for the escape of two prisoners at night. [Jewish] adults and children came from nearby kibbutz [sic] to watch us line up naked and laugh. To us this was most degrading.”

These accounts are small pieces of a larger whole. It is difficult to fathom the sheer scale of Palestinian dispossession that occurred during these early days of the Nakba. Of the 1.3 million Arabs who lived in Palestine before 1948, more than half would be uprooted from their homes. More than 500 Palestinian villages were depopulated, and dozens more were dismembered with armistice lines. During these operations, the Zionist authorities seized Palestinian property—lands, homes, businesses, gold, jewelry, cars—and then, claiming their owners to be “absent,” transferred them to the Jewish National Fund or the Israel Land Authority for exclusive Jewish use. (The United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine has estimated those losses at a value of more than $800 million in 1948 dollars, or more than $9 billion today.) And Israel has not slowed down; the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians persists as Israeli policies—land confiscation, discriminatory zoning and permit regimes, denial of residency, obstructing access to natural resources—facilitate forced population transfers. East Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley are being actively stolen by the Israeli state, in efforts financed by settler organizations like Elad and the settlement division of the World Zionist Organization.

For me, as for nearly all Palestinians, the Nakba is a part of an intimate family history. It dispossessed my four grandparents of their homes in Palestine, turning them into refugees. But the Nakba is also a part of our people’s present, because it never ended. A clear throughline connects the experiences of Palestinian life at the hands of Zionist forces in those early days to these programs today: a program of settler colonialism that seeks to own forest, stone, water, and soil. As the BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights has argued, the denial of reparations to refugees is itself part of the process of forced population transfer—it further destabilizes Palestinian families already burdened by the occupation, while ensuring that all the disappeared Arabs stay disappeared.

ONCE THE NAKBA IS UNDERSTOOD as an individual, communal, spiritual, and material maiming of the Palestinian people, it becomes clear that what is justified and necessary is not so-called reconciliation, but rather a program of decolonization. Practically, decolonization means the restoration of private and communal property expropriated by Zionists; an end to the occupation and reparations for the lives it has ruined; the release of all political prisoners; the liberation of Gazans from a brutal siege and blockade; the extension of full democratic rights under a single polity; accountability for the perpetrators of anti-Palestinian violence; programs of reparative and economic justice; and the return of refugees and their descendants.

This return of refugees—the foundational Palestinian demand—is a human right, recognized under international law for all displaced peoples, practically realized in Rwanda and Cyprus decades after displacement, and reaffirmed specifically for the Palestinians by the General Assembly of the United Nations more than 135 times since the Nakba. And operational proposals exist for this return. Abu Sitta says he has an exhaustive database of maps of Palestine prior to Zionist colonization, including depictions of the depopulated villages and detailed schematics for return. His approach involves a collective visioning; he brings Palestinians from across the world together to participate in an urban redesign campaign to draft plans for the repopulated villages, expanding them to handle the population growth since 1948, and outfitting them with modern water, sewage, electrical, and transportation infrastructure. His is just one example of these Palestinian efforts, long underway, which also include work by Munir Nuseibah to envision the facilitated return of displaced Palestinians in Gaza. These programs envision fair judicial processes for returning expropriated land and property—including, if necessary, the relocation of Israelis living in illegal settlements. In cases where relocation is infeasible, these approaches seek proper compensation for the lawful owners.

This return will not be easily achieved: The formal conditions of Israel as a state depend on the supremacy of the Jew and the subhuman status of the Palestinian—in law, in practice, in material relations. Zionists depict the decolonial project of Palestinian refugee return as tantamount to the “destruction of Israel.” In one sense, they are correct; a binational and democratic collective that does not enshrine the supremacy of the Jewish people over all others would indeed be the end of “Israel” as we know it. But it might also be the beginning of a world in which the destruction of Arab life is no longer permitted. The international community can assist this effort by boycotting, divesting from, and sanctioning Israel. For our part, Palestinians will continue to resist by any means necessary, until our return is secured.

To some, this beautiful vision of Palestinians once again in their homes and lands might seem frightening or dangerous—maybe even apocalyptic. Indeed, in the Hebrew Bible, God’s entrance into history is marked by destruction. Perhaps it is a feature of a fallen world that the arrival of justice would be registered as a kind of catastrophe.

A previous version of this essay stated that the PA’s access to funds from the Nita M. Lowey Middle East Partnership for Peace Act is contingent on not pursuing an ICC investigation; in fact, the restriction appears in a different part of the same appropriations bill and applies to a separate fund.

The previous version also included a claim from Salman Abu Sitta about the scale of the Nakba relative to other instances of ethnic cleansing. Because the terms of his analysis could not be adequately assessed, the quote has been removed.

Kaleem Hawa has written about art, film, and literature for The New York Review of Books, The Nation, The Times Literary Supplement, and other publications.