Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, October 2021, pp. 18-20

By Jonathan Kuttab

FROM ITS EARLY DAYS, Fatah was the largest Palestinian faction and viewed itself as the leader of the Palestinian national movement. It lacked a doctrinaire ideology, as most of the other factions had, and included political views that ranged from leftist Marxist, Leninists to conservative Muslim Brotherhood types. The late Yasser Arafat was fond of saying it was not a faction or party but a movement. The national movement of the entire Palestinian people.

After Fatah won the first elections held for the Palestinian National Authority, the confusion over the identity of Fatah increased since Arafat was the head of Fatah, the Palestinian Authority, and the PLO, to boot. The introduction of Fatah activists, who returned with Arafat into the political life of the West Bank, as prominent members of the new administration, or commanders of security forces further increased this confusion. In the security services, Jibril Rajoub and Mohammad Dahlan were appointed heads of the Preventive Security Forces in the West Bank and Gaza respectively. Other returning fighters were given positions in the different security services, of which there were 17 at one time.

In one interview I had with Jibril Rajoub, he indicated to me that while Palestinians from different factions, or no political affiliation, could be members of the new Palestinian government, the security forces had to be manned solely by Fatah loyalists.

As the PNA established itself and took on more and more civilian functions, jobs within the administration were increasingly doled out to Fatah activists as rewards for their loyalty, as well as to absorb returning PLO members and former prisoners into the service of the new government.

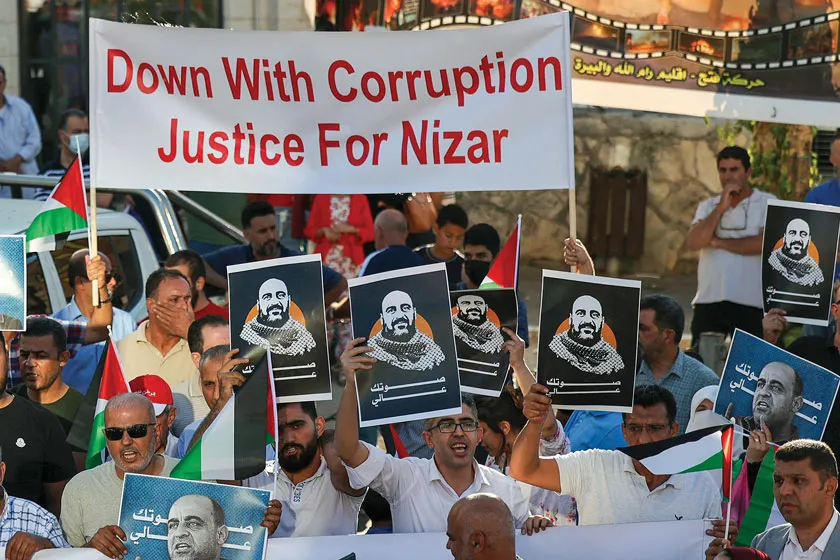

Palestinian protesters rally in Ramallah in the occupied West Bank on July 17, 2021, denouncing the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the aftermath of the death of activist Nizar Banat while in the custody of PA security forces. (PHOTO BY ABBAS MOMANI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES)

During this whole period, Fatah still maintained its separate identity. Its members often even carried out activities and attacks on settlers and Israelis without approval or coordination with the Palestinian Authority, which was duty bound under its agreements with Israel to scuttle and prevent such activities.

After the death of Arafat, and with the increasingly disappointing lack of progress of the “peace process” and the eventual suspension of the negotiations with Israel, a new situation arose. Activists in Fatah, who included former prisoners as well as returning PLO fighters, were getting jobs and positions within the Palestinian Authority, while leaving the actual opposition to the occupation to the PA in the form of negotiations with Israel. The rank and file were increasingly dissatisfied both with the conduct of the “national struggle” and with the corruption of reserving powerful positions for the older Fatah leadership. Yet the culture of viewing positions in government as rewards for loyalty, rather than positions of service to the people of Palestine was becoming part of the culture of Fatah, even though there was also a continuing disappointment and critique of such a culture as corrupt.

Calls for internal reforms and internal elections within Fatah finally resulted in holding Fatah internal elections in a party conference that was held in Bethlehem—the first in over 13 years. But the results were disappointing. Intensive behind-the-scenes lobbying led to lists that were predetermined by the existing leadership, and which reenforced and retrenched existing power centers. Local district elections for Fatah groups, which led to alternative lists, were ignored and only those who were favored by the existing leadership took positions. Factions in the inner circle of Mahmoud Abbas began forming, perhaps in anticipation of the power struggle that would take place when he either succumbed to his health problems, or old age. No “heir apparent” was either appointed, selected or identified.

Apart from the issue of corruption and factional loyalties, two substantive issues dominated the discussion within Fatah as well as the wider Palestinian population. One was the need for national reconciliation with Hamas and the second was the need to take effective action in confronting the occupation. The rank and file of Fatah, the prisoners, as well as the general population were adamant about the need to achieve reconciliation and a stronger unified position toward Israel. They also clamored for an end to “security coordination” with Israel, but the established leadership was reluctant to end the “security coordination.”

Security coordination with Israel was viewed as vital by Israel in preventing what it considered acts of terrorism against it and was viewed as the essential element in the whole agreement between Israel and the PLO, which led to the creation of the PA in the first place. Also, while it repeatedly stated it was in favor of reconciliation with Hamas, many within the Fatah leadership often acted as if Hamas was a greater enemy to it than Israel itself.

This state of internal confusion and paralysis came to a head with the recent call for general elections—after a 14-year hiatus.

Jibril Rajoub, with Egyptian support, made great steps in obtaining understandings with Hamas that paved the road for the elections to proceed. These included a promise by Hamas not to run a candidate for president, and to agree to holding the elections for the Legislative Council first, rather than simultaneously with the elections for president, as was their previous demand. Presidential decrees were issued which outlined the procedures for elections.

Lists began to form. As the elections drew closer, lists had to be filed with the elections board, and those lists revealed the loyalties of many influential members of Fatah as three separate lists associated with Fatah were fielded, and not just one official Fatah list. One list was associated with Mohammad Dahlan, a second with Marwan Barghouti, who is in an Israeli prison, but whose wife headed this second list, together with Nasser al-Qudwa, Yasser Arafat’s cousin, and the third was the official list associated with Abu Mazen himself. No ideological distinctions were apparent between the three lists, and the lists seemed to rest on personal connections, and buying influence.

However, all these efforts came to a grinding halt when Abu Mazen cancelled the elections, blaming Israel’s refusal to allow East Jerusalemites to participate in the elections. Most observers, however, think the real reason was his fear that elections may lead to advantages for Hamas over a still fragmented Fatah movement, particularly as it appeared that all three lists combined could not assure a Fatah majority in the upcoming elections.

The cancellation of elections was soon followed by the incidents in Sheikh Jarrah, and the attacks on Gaza. The combination of these events led to a plummeting in the reputation of the PA, which was seen as largely ineffectual if not collaborationist as it failed to offer any leadership, guidance, or participation in defending Jerusalem and the al-Aqsa mosque, while Hamas, even from its distant location in Gaza was able to claim participation in the struggle by shooting its largely ineffectual missiles toward Israel and sustaining heavy losses from the massive Israeli bombardment. The fact that the youths of Jerusalem acted on their own to defend al-Aqsa and Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan neighborhoods, and that the PA could not provide them with overt support, further deepened the crisis for Fatah, although some of its members doubtlessly joined the protest activities in Jerusalem, though not under the Fatah banner.

As criticism of the PA increased, its security forces in the West Bank committed yet another blunder. They came at night into an Israeli-controlled area (with obvious coordination with Israeli forces) and dragged a prominent critic of the PA, Nizar Banat, from his home and beat him to death. In the demonstrations that followed this crime, the PA sent into the streets massive numbers of its security forces, some in civilian clothes, who physically manhandled many prominent Palestinians, including women, and arrested and beat up others. They also fired into the air massively in a show of force. The effort was clearly intended to intimidate opponents, yet it led to even more anger and protests.

While Mahmoud Abbas felt that he was secure as long as the U.S. and the donor countries were pleased with him and his political line, his standing among his own people was constantly sinking, and his legitimacy now rested either on the money of the donors or the good will of Israelis, who granted permits and could ease travel and other restrictions. It did not help that the Israelis openly stated that their policy was to strengthen the PA and that they were giving work and travel permits specifically to strengthen the PA and weaken Hamas.

Not only that, but as the PA felt the anger and resentment of many, and that its influence among the population was weakening, it asked Fatah activists to go into the streets, with weapons, and demonstrate a popular support which it no longer had.

This created a major dilemma for many Fatah activists who were now totally uncomfortable not only with their sinking popularity, but with a real existential dilemma as to the nature and identity of their movement. Whether they liked it or not, they were now being totally identified with the PA and the security forces, and the failures of these bodies was reflecting directly on them. Yet many of them felt the same disappointment with the PA that the general population felt. They also wanted to see elections and democratization, and a prominent role in the fight against the occupation. At the same time, they felt the rivalry of Hamas and the other factions and did not want to give up the positions, jobs and privileges that came with being the “ruling party.”

While these subterranean trends dominate the thinking of Fatah activists, few expect any real changes until elections are held, if at all, or until the passing away of Mahmoud Abbas brings into the open the inevitable struggle for leadership both within Fatah, and the PA itself.

Jonathan Kuttab is a Palestinian human rights lawyer and peace activist. He is the co-founder of the human rights organizations Al Haq, the Mandela Institute for Political Prisoners, and the Jerusalem-based Palestinian Center for the Study of Nonviolence. He is also a board member of the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center in Jerusalem. His latest book, Beyond the Two-State Solution, is available from Middle East Books and More.