By Shane Quinn

American governments have intervened in dozens of countries globally since 1945, either directly by military invasions, indirectly through funding of elite opposition groups and stimulation of unrest, or covertly from its special services such as the CIA.

The level of US interference easily outweighs anything which can be attributed to the USSR or, later, Russia. (1) Among the core reasons behind the meddling pursued abroad by successive US administrations, is to ensure control over raw materials (oil, gas), strategically important areas (Latin America, Middle East, etc.) along with eliminating the threat of popular uprisings (Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, and so on).

The prominent American planner George Kennan (image on the right) summarised perfectly much of the thinking behind US foreign policy, when he wrote in a top secret State Department memorandum from February 1948 that,

“We need not deceive ourselves that we can afford today the luxury of altruism and world benefaction… We should cease to talk about vague and unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of the living standards and democratization”. (2)

Kennan was considered one of the liberal doves of his time, perhaps the most benevolent of US strategists.

The extent of American overseas intervention has, through living memory, left in its wake a sorry trail of human suffering only too well known to the victims, and little reported at home.

Yet the early roots behind these actions in fact precede both world wars, and lie mostly within the policies of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine. This credo, proposed first in December 1823 by James Monroe (1758-1831), America’s fifth president, espoused the right of US governments to intervene at will within its Latin American domains, whenever their interests were supposedly threatened by European rivals like Britain, Spain or Portugal.

The first glaring example of US imperial venture was executed during the attack on Mexico in the mid-1840s, so as to secure valuable reserves of cotton for American industry, mainly at the expense of the British. It was an ugly invasion also implemented on racial, expansionist grounds and which Ulysses S. Grant, future US president in the 1870s, described as “the most wicked war in history” and “I have always believed that it was on our part most unjust”. (3)

By 1848, around half of Mexican territory was permanently annexed to the United States, including well known regions such as California, Texas and Nevada.

All of the above actions were decided within the corridors of power in Washington, for the large part free from public judgment and analysis. By the time the Monroe Doctrine was put forth, 196 years ago, dark clouds were already gathering on the horizon.

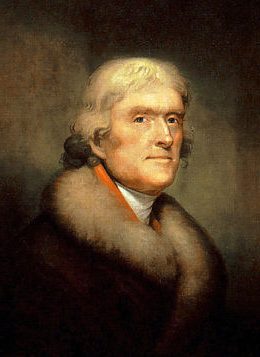

Former US president and Founding Father, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) – principal author of the 1776 Declaration of Independence – was, by the year 1816, issuing clear warnings about the direction that American democracy was taking. An alarmed Jefferson observed in 1816 that America “was moving toward a single and splendid government of an aristocracy founded on banking institutions and monied incorporations”.

If the trend were to continue, and it was just then beginning, Jefferson prophetically noted that “it would be the end of democracy and freedom. The few would be riding and ruling over the plundered plowmen and the beggared yeomanry”.

A decade later, 1826, Jefferson highlighted two separate groups, the “aristocrats” and the “democrats”; the first category consisting of “those who fear and distrust the people and wish to draw all powers from them into the hands of the higher classes” – and the second group, who “identify with the people, have confidence in them, cherish and consider them as the most honest and safe depository of the public interest, even though not the most wise”.

Jefferson hoped greatly that the bulk of the population would win out, and thereafter have extensive influence in the running of the nation. Aristocrats of this time were proponents of the budding capitalist state, figures whom Jefferson regarded with ample distaste and mistrust, as he identified the obvious contradiction between that of capitalism and democracy.

These viewpoints sound strange and almost extreme today, such has been the steady and unseemly drift towards what is now an absolutist, neoliberal state capitalist system, in which the public’s influence has been gradually eroded as to be almost negligible. Jefferson’s worst nightmares have unfolded.

Preceding Jefferson by a generation, Adam Smith (1723-1790), the famous 18th century British theorist and economist, was firmly opposed to what were then known as “joint stock companies”, in modern parlance: corporations, in their earliest stage.

Smith was pointedly against the evolution of big business, as he feared it would draw untold strength to its clutches and become “immortal persons”, with powers vastly exceeding ordinary people. This is precisely what occurred from the 19th century, particularly in the United States, the foremost capitalist country.

Smith also believed at the very essence of liberty was “the right of every workman to the fruits of his own labour”. Smith commented that should the worker become converted to a tool of production, he would have “no occasion to exert his understanding, or to exercise his invention”. As a consequence “he naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become”. (4)Foreign Power Intrusion in American Democracy? Guess Who?

A critical element in a person’s fulfillment is to work through one’s own intuition, freely and creatively without external authority or control. The development of natural, inherent qualities are difficult to attain in the typical modern working environment, much of which is in the hands of major corporate control – which are, it must be said, tyrannical institutions utterly unaccountable to public scrutiny.

The highly influential American philosopher and linguist, Noam Chomsky (image on the left), reveals that the rise of corporate power through government action “didn’t happen through the democratic process. It happened primarily through judicial decision, decision by lawyers and judges and so on, as part of the effort to create a developmental state, a powerful interventionist state that would introduce a high level of protectionism and direct public resources to private power, and in that way enable development to take place”. (5)

Smith himself, whose reflections Chomsky has often discussed, furthermore decried what he called “the vile maxim of the masters of mankind, all for ourselves, and nothing for other people”. This is an adage that has been one of the guiding principles taught over the past century or so; along with the “new spirit of the age: gain wealth, forgetting all but self”.

Smith further attacked the “merchants and manufacturers” in England that were “by far the principal architects” of policy, and who ensured their personal interests were “most peculiarly attended to”, no matter how “grievous” the result for the wider population, including victims of their “savage injustice” overseas in the British colonies.

Many of Smith’s views are supported in following decades by the Prussian philosopher and diplomat, Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), who affirms too, “if a craftsman creates something beautiful but does it on external command, by the orders of someone else and under coercion, we may admire what he does, but we will despise what he is, because he’s not human; he’s a machine”.

Humboldt believed that the state has a tendency to “make man an instrument to serve its arbitrary ends, overlooking his individual purposes”, and “To inquire and to create – these are the centres around which all human pursuits more or less directly revolve”. (6)

Humboldt expounds that,

“There is something degrading to human nature in the idea of refusing to let any man the right to be a man” (7); and he remarks, “Whatever does not spring from a man’s free choice, or is only the result of instruction and guidance, does not enter into his very being, but remains alien to his true nature; he does not perform it with truly human energies, but merely with mechanical exactness”.

The above are classical liberal expressions, opposed to all but minimal forms of state intervention or outside interference in society and personal life. This would seem quite alien to many of those regarding themselves as “liberals” in the present era.

Humboldt, another of the major classical liberal thinkers who has almost been forgotten, inspired the 19th century British philosopher John Stuart Mill.

These opinions are actually steeped in Age of Enlightenment ideals – an intellectual movement of especially high standard that existed roughly from the early 18th to the late 19th century; and which, in later eras, may have partly inspired extremely important intellectual figures like Chomsky, and preceding him, John Dewey (1859-1952).

Dewey, an American philosopher and educational reformer, recognised that the workers of a nation should be “the masters of their own industrial fate”, and not implements to be utilised by unelected, autocratic employers. Dewey’s insights are based on mainstream Enlightenment thinking, which developed long before the emergence of any “dangerous foreign ideologies” like Marxism or Leninism.

Dewey distinguishes that political policies are “the shadow cast on society by big business and, as long as that is so, the attenuation of the shadow will not change the substance”. Simply put, reforms and other mild antidotes are effectively useless. What is needed are large-scale popular revolts seeking to remove “the shadow”, and institute genuine public participation in policy; that is, real democracy.

With the regression in overall intellectual standards taking hold in the 20th century, the arguments and ideas expressed by Dewey were becoming isolated indeed.

Chomsky, one of the increasingly lone voices of reason from the second half of the 20th century onward, writes that the erosion of intellectual capabilities from the year 1900 and beyond “shows how much we have declined since Jefferson’s day… This should be part of intellectual history in a free society, the kind of thing that you ought to learn in elementary school. Jefferson’s distinction applies with precision to the modern age, except everything has been reversed and forgotten. This is also pretty standard in the academic culture”. (8)

To grant an insight into the steep decline in the 20th century, we can briefly examine figures like Walter Lippmann (1889-1974), a leading American intellectual and esteemed political scientist of his day. Lippmann stood as the most prominent individual in US journalism for around half a century.

Among other things Lippmann believed that, “We have to protect ourselves against the trampling and roar of the bewildered herd”, meaning the majority, whom he felt should be designated a “spectator” role in society, coming forth to “lend their weight” to “the responsible men” in “democratic elections”.

Lippmann thought that the governing of the country should be left to “the specialized class”, rather than to the “ignorant and meddlesome outsiders”, another of his flattering descriptions for the masses, who instead “must be put in its place”; which could be achieved through “the manufacture of consent”, in plain English, propaganda. (9)

As the 20th century advanced into the 21st century, with the neoliberal era strengthening its grip, about 70% of the American population have become disenfranchised, with little or no input upon public policy, the political arena or the media they consume. To provide an example, the US has “one of the worst election processes in the world, and it’s almost entirely because of the excessive influx of money”, according to former US president Jimmy Carter in 2012.

The situation is not much more favourable in the many other capitalist “democracies” prevalent in the Western hemisphere, and also throughout much of mainland Europe and elsewhere.

Chomsky discerned that,

“Effective power is indeed in the hands of the higher classes. The early institutions, banking institutions and monied incorporations that he [Jefferson] was concerned about are now in vast power and control and dominate the decision-making system, essentially in secret. Modern democratic theory, interestingly, has veered very sharply from Jeffersonian ideas, and in fact is precisely based on fear and distrust of the people”. (10)

The current form of state capitalism is often rather grotesquely called “liberal democracy”. Classical liberalists would quite likely be appalled.