NOVANEWS

When Nate and his sister were children, their grandparents brought them to the US from a rural farm town in Belize. They were fleeing domestic violence: Their father was a powerful government official who often threatened them.

“We came over here legally at first,” Nate recalled. “We flew over on a plane and met my mother in Oklahoma, where she already had a home and a job.”

He and his family had visas and passports, and were cleared to set foot on US soil. But when he turned 18, his visa expired and he hadn’t been naturalized. Going back to Belize wasn’t a safe or feasible option for Nate (his name has been changed to protect his identity). His queer identity could put him at risk; gay intimacy was outlawed in the Central American country until 2016. Plus, he’d established a life and identity rooted in the US But navigating life here without government-issued documentation has come with a different set of challenges.

In addition to the more egregious forms of oppression many undocumented immigrants face, Nate has contended with being unable to do everyday tasks, such as opening a bank account, cashing checks, and applying for jobs and housing. “I’ve found ways around it because a lot of people in my community have known me since I was a kid,” he said. Racial perceptions have also shielded him because people often assume he is Black American. But still, he says that he “would benefit greatly from having a government ID.”

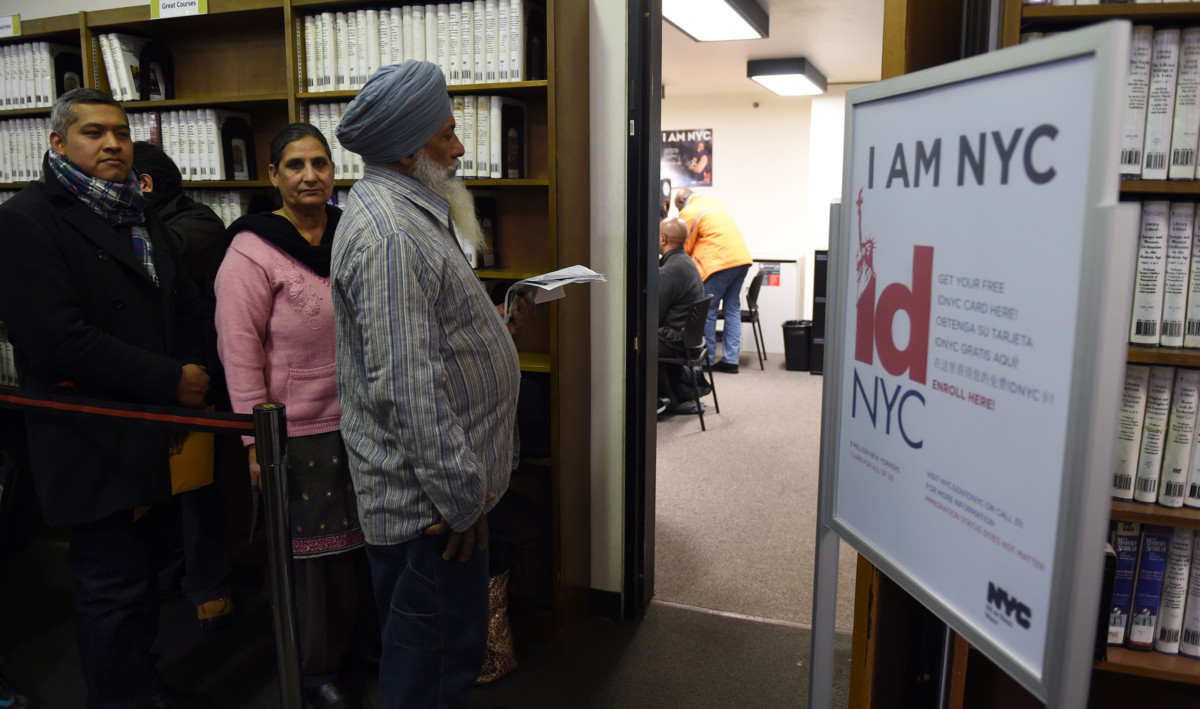

With people like Nate in mind, more than 20 US cities and counties have launched municipal identification programs since 2007 to make civic engagement and day-to-day living more accessible. Several more are in the process of creating legislation that would allow residents of any immigration status to get a local government ID.

Poughkeepsie, New York, is the latest city to pass a municipal identification program into law, and the first city to do so with a Republican mayor in office. The Poughkeepsie Common Council voted unanimously in July to launch the new program, which was made possible in part by the advocacy and lobbying efforts of Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, a membership-based grassroots movement combating issues faced by mostly working-class communities of color in the Hudson Valley region. For the members of the organization, the issue of safety and access for immigrants in their communities is a very personal one.

“We came over here legally at first,” Nate recalled. “We flew over on a plane and met my mother in Oklahoma, where she already had a home and a job.”

He and his family had visas and passports, and were cleared to set foot on US soil. But when he turned 18, his visa expired and he hadn’t been naturalized. Going back to Belize wasn’t a safe or feasible option for Nate (his name has been changed to protect his identity). His queer identity could put him at risk; gay intimacy was outlawed in the Central American country until 2016. Plus, he’d established a life and identity rooted in the US But navigating life here without government-issued documentation has come with a different set of challenges.

In addition to the more egregious forms of oppression many undocumented immigrants face, Nate has contended with being unable to do everyday tasks, such as opening a bank account, cashing checks, and applying for jobs and housing. “I’ve found ways around it because a lot of people in my community have known me since I was a kid,” he said. Racial perceptions have also shielded him because people often assume he is Black American. But still, he says that he “would benefit greatly from having a government ID.”

With people like Nate in mind, more than 20 US cities and counties have launched municipal identification programs since 2007 to make civic engagement and day-to-day living more accessible. Several more are in the process of creating legislation that would allow residents of any immigration status to get a local government ID.

Poughkeepsie, New York, is the latest city to pass a municipal identification program into law, and the first city to do so with a Republican mayor in office. The Poughkeepsie Common Council voted unanimously in July to launch the new program, which was made possible in part by the advocacy and lobbying efforts of Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, a membership-based grassroots movement combating issues faced by mostly working-class communities of color in the Hudson Valley region. For the members of the organization, the issue of safety and access for immigrants in their communities is a very personal one.