NOVANEWS

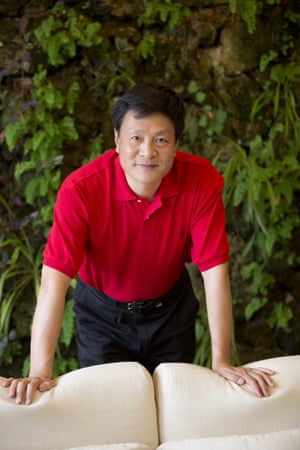

Yu is the founder and dean of the school of landscape architecture at Peking University, founding director of architectural firm Turenscape, and famous for being the man who reintroduced ancient Chinese water systems to modern design. In the process he has transformed some of China’s most industrialised cities into standard bearers of green architecture.

Yu’s designs aim to build resilience in cities faced with rising sea levels, droughts, floods and so-called “once in a lifetime” storms. At 53, he is best known for his “sponge cities”, which use soft material and terraces to capture water which can then be extracted for use, rather than the usual concrete and steel materials which do not absorb water.

European methods of designing cities involve drainage pipelines which cannot cope with monsoonal rain. But the Chinese government has now adopted sponge cities as an urban planning and eco-city template.

Yu spoke in Melbourne on Tuesday at a symposium on water-conscious design held as part of Melbourne DesignWeek at the National Gallery of Victoria. Speaking to Guardian Australia ahead of his appearance, Yu, who is based in Beijing, explained the key benefit of sponge cities is the ability to reuse water. “The water captured by the sponge can be used for irrigation, for recharging the aquifer, for cleansing the soil and for productive use,” Yu said.

“In China, we retain storm water and reuse it. Even as individual families and houses, we collect storm water on [the] rooftop and use the balcony to irrigate the vegetable garden.”

When it comes to water, the mottos of the sponge city are: “Retain, adapt, slow down and reuse.”

His firm now has 600 employees and works across 200 cities in China. The firm has completed more than 600 projects and won a swag of major architecture and design awards.

The strategies Yu uses are “based on peasant farming techniques, adapting peasant irrigation systems to urban environments and experience in adapting buildings to a monsoon climate”.

The first strategy – “based on thousands of years of Chinese wisdom” – is to “contain water at the origin, when the rain falls from the sky on the ground. We have to keep the water”.

“In China, there is a shortage of fresh water,” Yu says. “China has only 8% of fresh water of the world and feeds 20% of the population – so any fresh water from the sky will need to be kept in an aquifer.”

Yu, who grew up on a farm and later studied architecture at Harvard, understands the need to be water conscious. “The ability to regulate water year-round in dry season is a very critical strategy for the people to survive.

“One thing I learned is to slow down the process of drainage. All the modern industrial techniques and engineering solution is to drain water away after the flood as fast of possible. So, modern tech is to speed up the drainage but ancient wisdom, which has adapted in the monsoonal season, was to slow down the drainage so the water will not be destructive anymore. By slowing the water it can nurture the habitat and biodiversity.”

For Australia, and places where water is scarce: “When it’s dry, keep the water on the ground in an aquifer, so it will not evaporate too much.”

Adaptation to drought conditions is also important: using as little water as possible, and recycling what there is.

As Yu says, it’s important to “make friends with water”. “We don’t use concrete or hard engineering, we use terraces, learned from ancient peasantry wisdom. We irrigate. Then the city will be floodable and will survive during the flood. We can remove concrete and make a water protection system a living system.”

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.Thomasine, Sweden