BYRimsha Syed,

PART OF THE SERIES

The Road to Abolition

Muslim groups across Wisconsin and from Washington, D.C., joined together soon after the police-perpetrated shooting of Jacob Blake to issue a joint statement saying, “Yet again, police officers committed horrifying, infuriating violence against a Black person.… We condemn this police shooting and demand a thorough investigation in order to bring justice to Blake and his family.”

Blake was shot in the back seven times by Kenosha police officers on August 23, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down, with injuries to his kidney, liver, spinal cord, stomach, intestines and more.

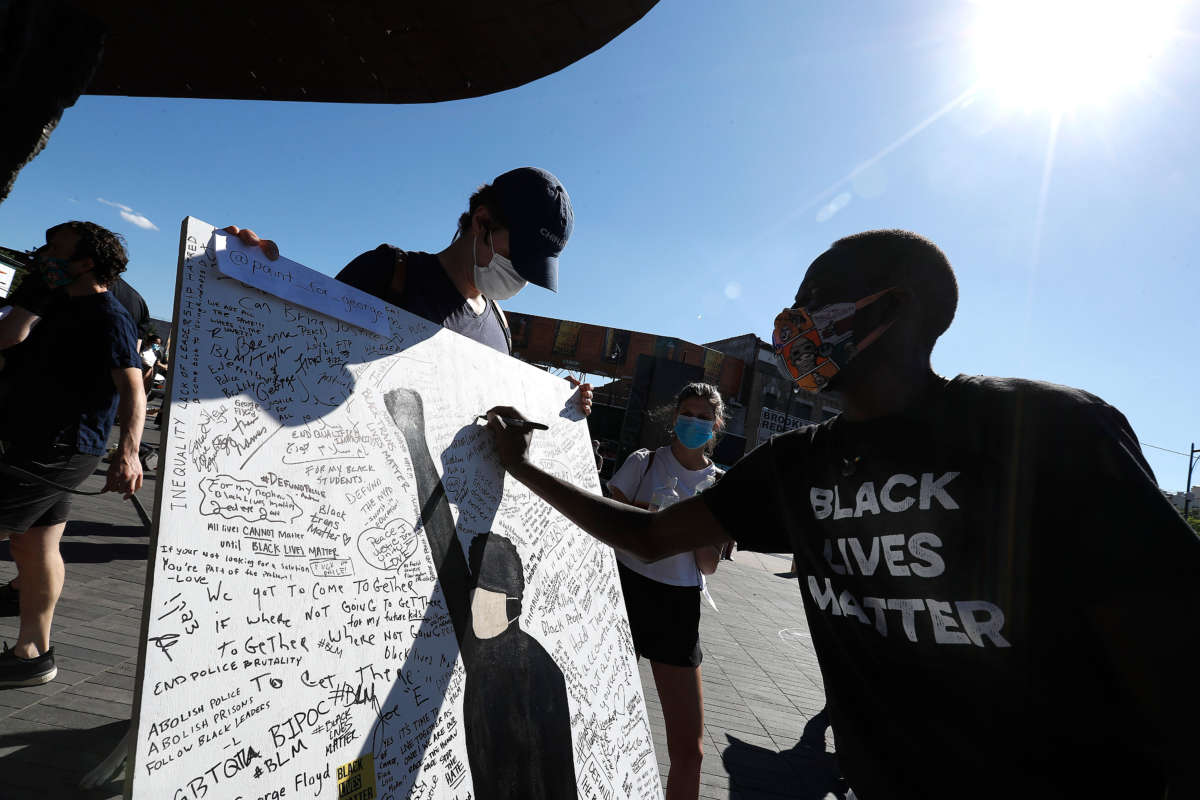

Muslim groups’ rapid condemnation of the shooting of Blake comes after a spring in which many Muslims joined in on powerful demonstrations against systemic racism across the United States following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers on May 25.

Following the murder of Floyd, many Muslim Americans had been asking why workers at Cup Foods, which is owned by a Muslim immigrant family, called the cops in the first place. New discussions and disagreements about Black and Muslim solidarity also helped to expose the anti-Black sentiments still harbored in many South Asian and Arab Muslim families.

The Black-led, youth-led protests that have risen up in the past several months — alongside the decades-long work of Black women abolitionists like Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Mariame Kaba — have ignited global conversations around abolition as the complete dismantling of the policing system. In short, “abolition” seeks to build a world in which we do not rely on anti-Black, white supremacist institutions to oversee society. While high-profile politicians attempt to push reformist policies, like giving police departments $300 million for body cameras, self-determination cannot come from a system that continues to imprison, surveil, terrorize and murder Black communities.

Police abolitionists have long fought for defunding local police and redistributing that money toward education, housing, food and other necessities as a true means to confront neighborhood violence. It is critical for Muslim communities to envision this model on a global scale and demand that the trillions spent on weapons, some of which are being used by the Israel Defense Forces to colonize more Palestinian land, be reallocated to the needs of the community.

In spite of the fact that one-third of the U.S. Muslim population is Black, non-Black Muslims often don’t consider anti-Black racism, mass incarceration, or police brutality as “Muslim” issues. Not only are mosques deeply segregated by race and class, but many non-Black Muslims have no knowledge of the anti-Black racism in policing.

Kenyatta Bakeer, a senior trainer at the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative, said that it’s been heartening to “see the surge of non-Black people” getting engaged in the movement against anti-Black police violence, “as they awaken regarding the light being shown on anti-blackness,” but that some efforts still feel “performative” rather than doing work that goes beyond meaningless messages or words.

“I am a born and raised Black American Muslim,” Bakeer added. “I grew up in a primarily Black Masjid and it wasn’t until my father took me to an Indo Pak [Indian-Pakistani] Masjid [mosque] when I was in college, at the age of 21, when I encountered bias and being shunned by non-Black Muslims. I just thought it was because of a difference in culture. I didn’t really process it, until years later when I went to another non-Black Masjid.”

In mid-June, a few weeks after the mass mobilization against police brutality, the East Plano Islamic Center in Plano, Texas, partnered with the city’s police department to hold a panel discussion called “Systemic Racism – An Open Discussion about Policing Policies with Plana Police Chief.” A petition was created mere seconds after the lecture was publicized that now has over 50,000 signatures. Many Muslims across the globe pleaded for the East Plano Islamic Center to cancel the event, highlighting the hypocrisy of giving the police a platform instead of listening to the demands of Black organizers. Instead, the East Plano Islamic Center reached out to Imam Khalid Shahid, of Masjid-al-Islam, a historically Black mosque in Dallas, in an effort to mollify the masses of Muslims who agreed that this event was not in line with the demands of the Black Lives Matter movement. Imam Shahid made comments such as, “I’m not saying the police are perfect,” and the event went on as planned.

“It’s unfortunate that the Islamic Center chose to seek out one Black imam to validate their poor decision to host this event against their community members’ wishes,” said Shandraya Rogers, a community member involved with the East Plano Islamic Center, adding that if the center “truly wants to end police brutality and other forms of systemic racism in this country, I encourage its leadership to give their Black community members the same opportunity and platform that was given to the police chief of Plano.”

Alliances between mosques and their local police departments are not uncommon, given that Muslim communities are reliant upon law enforcement to readily combat Islamophobic threats, vandalism, or other unsafe events. But in a period of history in which conversations around the outright abolition of police are widespread, it’s time for Muslim communities to re-evaluate their connection to law enforcement.

In the same vein, it’s important to note that law enforcement’s targeting and surveillance of Muslim communities is an inseparable part of police violence. The Obama administration’s so-called Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programs continue to give police departments across the nation funds to monitor Black Muslim communities, leading to a generation of armed cops who characterize Black Muslim youth as extremists based on both their race and religion. While Black youth are at the forefront of demonstrations across the U.S., CVE programs have equipped cops to equate rightful resistance with criminality. Piecing together the position of Black Muslims through U.S. history can help not only to highlight how stealthy surveillance programs can adapt with time but also to highlight what that means for Black Muslims today.

COINTELPRO (an acronym for Counterintelligence Program) was the official name of the project conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation to spy on, infiltrate, discredit, disrupt and destruct domestic organizations and individuals it considered “subversive.”Although COINTELPRO officially ended in 1971, similar counterterrorism or surveillance programs exist to threaten communities of color using surplus military weapons and procedures learned from the Israel Defense Forces. The creation of both the Department of Homeland Security and Denaturalization Section of the Department of Justice, which strips rights from naturalized citizens if they are convicted of certain crimes, are just a few examples of how counterterrorism has worsened the lives of Black and Muslim people.Islamic liberation is indistinguishably linked to the journey of abolition. There is no room for police in our mosques or in our hearts.

In the face of decades-long surveillance and violence, asking mosques to discard their relationships with law enforcement isn’t easy. However, abolition offers a compelling perspective that offers communities the chance to take safety into their own hands, rather than believing that surface-level reforms will make us human in the eyes of imperialist aggression. Islam compels us to imagine justice, freedom and liberation. Islam also demands us to stand against oppression, which is why it is not enough to say “Black Lives Matter” without action to change ourselves, our mosques and our communities.

“It is my understanding that police presence in any space where marginalized communities reproduce or replicate causes the same carceral harm either in their communities or in closer spaces,” said Queen-Cheyenne Wade, an organizer, educator and cofounder of the Greater Boston Marxist Association. “We, in Boston know the police here do not keep our Black Muslim youth safe, and many of our community leaders and spaces act accordingly in efforts of community, safety and solidarity in the face of police violence and surveillance.”

Young Muslim organizers draw heavily on Angela Davis’s work and the connections it draws between policing, the prison-industrial complex and capitalism. Capitalism is evidently antithetical to Islam, identifying the role that abolition plays in our faith. It is our duty to vehemently stand for justice by acknowledging that Islamic liberation is indistinguishably linked to the journey of abolition. There is no room for police in our mosques or in our hearts. Queen-Cheyenne Wade reminds us that the Quran contains many surahs recounting those who sustain their greediness by oppressing others, like Surah Al-Masad.

“As an abolitionist, I understand this work as not only the dismantling and abolition of police systems, but of all systems that are created with the intention of harm and exploitation of Black peoples and other communities of color,” said Queen-Cheyenne. “To look away from these injustices is a direct betrayal to our understanding of God’s truth about human connectedness.”