NOVANEWS

www.lalkar.org

Nov-Dec 2015

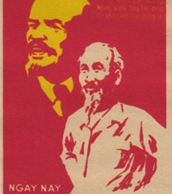

The Vietnam War: Reasons for Failure – Why the U.S. Lost

30 April this year marked the 40th anniversary of the historic victory of the Vietnamese people against US imperialism, whereas the 19 th of May marked the 125thanniversary of the birth of Ho Chi Minh, the great leader of the Vietnamese people. To mark these two events, Carlos Martinez wrote two articles, the first of which, i.e., his article on the liberation of Saigon, resulting in the total defeat of US imperialism in Vietnam and the consequent reunification of the country, appeared in the July issue of LALKAR.. The other article, which contains extremely useful and informative material on the long, multi-faceted, revolutionary life of that great internationalist, Ho Chi Minh, is now reproduced below.

People of Ho Chi Minh’s calibre don’t come around often. One of the great revolutionaries of the twentieth century, he excelled as a leader, a teacher, a journalist, a strategist, an internationalist, a unifier, a guerrilla fighter, a negotiator, a creative thinker, a poet. He endured decades of exile and then decades of war. He suffered prison and torture in China in the early 1940s (by which time he was already in his fifties). As a guerrilla leader and then as the president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam under attack from French colonialism, he lived with his comrades in the most basic possible conditions in the caves of Cao Bang, often having to forage for food. And yet, his dedication to the causes of Vietnamese independence, Vietnamese unification, and global socialism never faltered. With relentless energy, profound intelligence and undying passion, he led his people through every up and down over the course of half a century.

His most notable achievements include:

Providing the major inspiration and strategic vision for the Vietnamese Revolution from the early 1920s up until his death in 1969.

Connecting the Vietnamese indepen-dence struggle with the global socialist and anti-imperialist movement, and thereby providing it with a source of decisive support.

Uniting different political trends and backgrounds into a single, extremely effective fighting organisation.

Purposefully building and training a close-knit team of serious revolutionaries capable of providing leadership to the Vietnamese masses.

Promoting and building maximum national unity against imperialism, bringing the peasantry, working class, intellectuals and patriotic capitalist elements together in order to struggle against French, Japanese and US colonialism.

Along with the other top leaders of the Vietnamese resistance, consistently making a correct analysis of the prevailing balance of forces, enabling historic victories such as the capture of power in August 1945, the defeat of the French occupation in 1954, the building of socialism in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), and the Tet Offensive of 1968, which served as the major turning point in the war with the US.

Leading the work of inspiring, organising and educating the masses of the Vietnamese people for their long struggle against imperialism and for socialism.

With very good reason, ‘Uncle Ho’ continues to be revered, loved and studied in Vietnam, and his legacy remains a source of profound inspiration for anti-imperialists throughout the world. However, given how great a role he played, surprisingly few people know anything about him other than that he was the leader of the Vietnamese Revolution and that he once said “nothing is more precious than independence and freedom.” Therefore, in writing this article (which is published on the 125th anniversary of Ho’s birth), I try to give some insight into his legacy, focusing in particular on his first few decades of activity and on those events that served to shape his ideas and strategy – and in turn the course of the Vietnamese revolution.

The article is followed by a selection of quotes that I hope the reader will find useful.

For any reader looking for more detail, the best place to start is unquestionably Ho Chi Minh’s selected works, which tell the story of the Vietnamese Revolution better than any other book. The well-known biographies by western authors William Duiker and Jean Lacouture are both very useful, although they’re not written from a communist or anti-imperialist perspective. Duiker in particular has done a huge amount of painstaking work to dig out the details of Ho’s life – a job made very difficult by the fact that Ho operated for much of his life in conditions of strict secrecy, in many different countries, using dozens of pseudonyms. The biographies by Ho Chi Minh’s comrades-in-arms Pham Van Dong and Truong Chinh will strike most western readers as being overzealous in their praise, but they nonetheless contain useful insights and moving recollections, as does the collection of articles entitled ‘Reminiscences of Ho Chi Minh’.

Evolution of a revolutionary

Nguyen Sinh Cung, as he was then called, was born on 19 May 1890 in the tough mountain terrain of Nghe An. His father was a scholar, well-respected but penniless as a result of his opposition to French colonial rule. Ho Chi Minh was raised in a spirit of patriotism and with a deep respect for the Vietnamese heroes of past centuries who had waged long and bitter struggles against foreign domination. As a student in Hue in the first decade of the twentieth century, he became involved in the protest movement against the brutality of the French occupiers. In order to avoid arrest for his activism, he went south to Saigon – at that time the capital of the French colony of Cochin China – from where he decided to go abroad. Working on ships, he spent two years at sea. William J Duiker, in his exhaustive biography Ho Chi Minh – a life, (Hachette UK, 2012), writes:

Exposure to the world outside Vietnam had a major impact on his thinking and attitude toward life. Over a decade later, when he began to write articles for French publications, his descriptions of the harsh realities of life in the colonised port cities of Asia, Africa, and Latin America were often shocking, dealing with the abject misery in which many people lived and the brutality with which they were treated by their European oppressors. By the beginning of the twentieth century, much of the world had been placed under colonial rule, and the port cities of Africa and Asia teemed with dockworkers, rickshaw pullers, and manual labourers, all doing the bidding of the white man. It may have been during this period of travel abroad that the foundations of his later revolutionary career were first laid.

After working for some months in New York and Boston (including, in the latter city, at the same hotel at which Malcolm X worked some thirty years later!), Ho Chi Minh came to London, where he worked in various kitchen jobs and came into contact with Marxist ideas for the first time. Whilst in London, he found out about the Irish independence struggle and became an agitator for that cause. Writing in 1920 about the death on hunger strike of the Irish Republican leader Terence MacSwiney (in Brixton Prison), he wrote: “A nation that has such citizens will never surrender” (see Peter Berresford Ellis, A history of the Irish working class, Pluto Press, 1996). Ireland’s epic anti-colonial struggle became an inspiration, and helped to refine Ho Chi Minh’s strategic thought in relation to the situation in Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh arrived in France around the time of the end of the First World War and quickly established contact with the Vietnamese community there, as well as with French socialists and communists, and members of numerous exiled and immigrant communities from other colonies, including Korea, China, Algeria, Madagascar and the French colonies of West Africa. Adopting the name Nguyen Ai Quoc (Nguyen the patriot), he started to write passionately and copiously. As his reports and declarations seeped back into Indochina (under which name Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were collectively administered by France), the name Nguyen Ai Quoc increasingly inspired curiosity, then support, then loyalty from the people of Vietnam, suffering as they were under the heel of France’s ‘civilising mission’ – a civilising mission that denied people the right to education, to land, to decent working conditions, to even the most basic forms of democracy; a ‘civilising mission’ that promoted opium addiction as a means of pacifying the masses and enriching the colonisers.

Global struggle against imperialism and for socialism

In France, Ho Chi Minh was introduced by French communists to the key elements of revolutionary ideology. In a small library in Paris, he devoured Marx’s Capital and other classic texts. However, he soon came to see some of the problems and contradictions afflicting the French communist and socialist movement – problems that, a century later, continue to afflict the left in Western Europe and North America. Focused exclusively on the class struggle in France, they knew little of the anti-colonial struggle and didn’t have a consistent policy regarding liberation of the colonies.

This was around the time of the founding of the Communist International (variously known as the Third International and the Comintern), made necessary by the descent of its predecessor (the Second International) into what Lenin referred to as social chauvinism: a position of collaboration with, and support for, the various capitalist governments in pursuit of the First World War. This war was, after all, an imperialist war; a war based on competition between different imperialist powers for control of the colonies. The revolutionary position put forward by the Bolsheviks and a handful of others was: refuse to cooperate with the war, take advantage of the crisis to defeat capitalism in Europe, and help to bring about freedom for the colonies. In a short but profound and moving article called ‘ The path which led me to Leninism‘, Ho Chi Minh discusses his trajectory as a revolutionary and how he came to be totally aligned with the Third International.

“What I wanted most to know was: which International sides with the peoples of colonial countries? I raised this question – the most important in my opinion – in a meeting. Some comrades answered: It is the Third, not the Second International. And a comrade gave me Lenin’s ‘Thesis on the national and colonial questions’ published by L’Humanité to read. There were political terms difficult to understand in this thesis. But by dint of reading it again and again, finally I could grasp the main part of it. What emotion, enthusiasm, clear-sightedness and confidence it instilled into me! I was overjoyed to tears. Though sitting alone in my room, I shouted out aloud as if addressing large crowds: ‘Dear martyrs, compatriots! This is what we need, this is the path to our liberation!’”

“After that, I had entire confidence in Lenin, in the Third International. Formerly, during the meetings of the Party branch, I only listened to the discussion; I had a vague belief that all were logical, and could not differentiate as to who were right and who were wrong. But from then on, I also plunged into the debates and discussed with fervour. Though I was still lacking French words to express all my thoughts, I smashed the allegations attacking Lenin and the Third International with no less vigour. My only argument was: ‘If you do not condemn colonialism, if you do not side with the colonial people, what kind of revolution are you waging?’”

On the basis of his ground-breaking study of imperialism, and seeing how imperialist profits had allowed the European capitalists to ‘buy social peace’ and bribe much of the working class leadership, Lenin came to understand that the anti-colonial struggle was a crucial part of the global struggle for socialism. Armed with this understanding, the Soviet Union became a massive ‘liberated territory’ for the anti-colonial struggles, and the Third International updated Marx’s slogan “Workers of the world, unite” to read: “Workers and oppressed peoples of the world, unite!”

Thus, in the age of imperialism, the liberatory ideas expressed in the Communist Manifesto had become relevant not just to the working class of Europe but also to the oppressed and downtrodden people of the entire world. Ho Chi Minh was the first Vietnamese, and one of the first globally, to fully understand the significance of this and to apply it to his own nation’s liberation struggle. For the remaining five decades of his life, he would stay true to the principle of the unity of the global struggle against imperialism and for socialism. With his uncanny ability to sum up political ideas in a simple way, he said:

” Capitalism is a leech with one sucker on the working class in the imperialist countries and the other on the oppressed peoples of the colonies. To kill that leech, its two suckers must both be cut off. If only one sucker is removed, the other will continue bleeding the workers white and the leech will still be alive and grow a new sucker” (quoted in Tap Chi Cong San, Ho Chi Minh’s ideology and the Vietnamese revolutionary path, The National Publishing House, Hanoi,1997, p.298).

Internationalist

In France, Ho Chi Minh set up a journal called Le Paria (The Pariah), which from 1922 to 1926 was a leading voice for the anti-imperialist struggle. Copies were smuggled into Indochina, providing a first window into the world of global revolution for people whose access to information was severely limited by French censorship. One biographer of Ho Chi Minh, the French journalist Jean Lacouture, comments of Ho’s writing at the time that “the remarkable thing … is the global conception of the problem of the oppressed, the constant determination not to isolate what was only one of many colonial questions.”

Late in 1923, having earned a reputation for himself as a capable and fiery propagandist against colonialism, the young Nguyen Ai Quoc [Ho Chi Minh] had the chance to travel to the Soviet Union. Given work at the Far Eastern Bureau of the Comintern, he quickly became an important and popular figure in Moscow, providing valuable information about the situation of the Indochinese people and their sufferings under French colonialism. In Moscow he became friends with several key figures of the international movement, including Georgi Dimitrov (later the General Secretary of the Comintern and first leader of post-war Bulgaria) and Zhou Enlai (a top leader of the Chinese Revolution and first Premier of the People’s Republic of China from 1949 until his death in 1976).

Towards the end of 1923, Ho enrolled at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, at which there were then over a thousand students from 62 different countries. “As Nguyen Ai Quoc described it in his article, the school was an idyllic place to study. There were two libraries containing over forty-seven thousand books, and each major nationality represented at the school possessed its own section with books and periodicals in its own national language. The students were ‘serious and full of enthusiasm’ and ‘passionately longed to acquire knowledge and to study.’ The staff and the instructors treated the foreign students ‘like brothers’ and even invited them to ‘participate in the political life of the country’” (Duiker). The experiences studying, and later teaching, at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East undoubtedly helped to cement the ideas of the budding revolutionary Nguyen Ai Quoc.

In Moscow, Ho was disappointed to find that not all personalities and parties of the Comintern – including the party of which he was a founder member, the French Communist Party – were living up to Lenin’s demand to highlight and support the anti-colonial struggle. Taking the floor at the Fifth Congress of the Comintern in June 1924, he reiterated the importance of workers in the ‘metropolis’ joining hands with oppressed peoples: “You all know that today the poison and life energy of the capitalist snake is concentrated more in the colonies than in the mother countries. The colonies supply the raw materials for industry. The colonies supply soldiers for the armies. In the future, the colonies will be bastions of the counterrevolution. Yet in your discussions of the revolution you neglect to talk about the colonies… Why do you neglect the colonies, while capitalism uses them to support itself, defend itself, and fight you?” (cited in Duiker). Specifically pointing to the hypocrisy of the west European parties, he added: “As for our Communist Parties in Great Britain, Holland, Belgium and other countries – what have they done to cope with the colonial invasions perpetrated by the bourgeois class of their countries? What have they done from the day they accepted Lenin’s political programme to educate the working class of their countries in the spirit of just internationalism, and that of close contact with the working masses in the colonies? What our parties have done in this domain is almost worthless. As for me, I was born in a French colony, and am a member of the French Communist Party, and I am very sorry to say that our Communist Party has done hardly anything for the colonies.”

Throughout his life, Ho would struggle consistently against this weakness he saw in the western left: its adherence to a narrow, pre-Lenin, eurocentric version of Marxism that sees the world purely in terms of the battle between workers and capitalists in the west, ignoring the key questions of imperialism and national oppression. It’s worth pointing out that, sadly, this weakness is not some sort of historical relic, confined to the ‘bad old days’. Indeed it is still decidedly recognisable today, in an era when huge numbers of supposed socialists and communists in the west refuse to side with peoples under attack from the imperialist powers (Syria, Libya and Ukraine come to mind).

At the Comintern Congress, Ho Chi Minh also took the opportunity to highlight the revolutionary role that could and would be played by the peasantry in the colonies:“Famine is on the increase and so is the people’s hatred. The native peasants are ripe for insurrection. In many colonies, they have risen many times but their uprisings have all been drowned in blood. If at present the peasants still have a passive attitude, the reason is that they still lack organisation and leaders. The Communist International must help them to revolution and liberation.”

Towards the end of 1924, Ho left Moscow to work in China on behalf of the Comintern, on a mission to support the Chinese Communist Party. Based in Canton, he was able to link up with a number of young Vietnamese revolutionaries, many of whom continued to be part of the nucleus of Vietnam’s anti-colonial struggle for decades to come. In 1925, a small group called the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League was formed by Ho and a few of his comrades; this was the first Vietnamese communist organisation. Over the course of two years in Canton, Ho Chi Minh acted as teacher and organiser, making contact with as many Vietnamese revolutionaries as he could, and running a school for training them in ideology and organisational skills. “He taught his charges how to talk and behave in a morally upright manner (so as to do credit to the revolutionary cause), how to speak in public, how to address gatherings of workers, peasants, children, and women, how to emphasise the national cause as well as the need for a social revolution, how to behave without condescension to the poor and illiterate. He anxiously checked on their living and eating conditions to make sure that they were healthy and well cared for; when they were gloomy and despondent, he cheered them up. One ex-student recalled his incurable optimism. When students appeared discouraged at the petty corruption of Vietnamese mandarins and the general ignorance and lethargy of the village population, he replied, ‘It’s just these obstacles and social depravity that makes the revolution necessary. A revolutionary must above all be optimistic and believe in the final victory’” (Duiker).

Ho and his comrades in the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League set up a journal, Thanh Nien, which was issued weekly and sent into Vietnam by sea. Between 1925 and 1930, over 200 issues were published, allowing Ho Chi Minh to systematically agitate, educate and organise significant numbers of people inside Vietnam itself. By the late 1920s, the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League had around two thousand members inside Indochina, and more in China, France and elsewhere. In his period of editing Thanh Nien, Ho perfected his ability to communicate a version of revolutionary Marxism that was understandable and acceptable to ordinary Vietnamese peasants and workers. His style is simple but powerful, as can be seen from the following example:

“The workers and peasants are the leading force of the revolution. This is because, first, the workers and farmers are more heavily oppressed; secondly, the workers and peasants are united and therefore possess the greatest strength; and thirdly, they are already poor; if defeated, they would only lose their miserable life; if they win, they would have the whole world. That is why the workers and farmers are the roots of the revolution, while the students, small merchants, and landowners, though oppressed, do not suffer as much as the workers and farmers, and that is why these three classes are only the revolutionary friends of the workers and farmers .” (Ho Chi Minh – The Road to Revolution (1926))

The work in Canton was very fruitful, but it was brought to an abrupt end when Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek initiated his vicious purge in April 1927. Thousands of communists were rounded up and murdered in Shanghai and Canton, thus finishing off the Communist-Kuomintang alliance (until 1936, when Chiang was forced to cooperate again with the Communist Party in the war of resistance against Japan). Ho escaped Canton just hours before his office was raided, and made his way to Hong Kong. From there, he travelled to Paris, Brussels and Berlin for various conferences and consultations, before heading back to Asia. He arrived in Siam (now Thailand) in mid-1928, and began organising among the large Vietnamese exile community there.

Around a year later, he heard that the revolutionary movement in Vietnam was descending dangerously into sectarianism and internal conflict. He travelled immediately to Hong Kong, where he called together the competing factions, arbitrated the various disagreements, and called for the existing revolutionary organisations to be disbanded and replaced with a single new party: the Indochinese Communist Party. The inaugural meeting of the ICP took place on 3 February 1930, and agreed a ten-point programme calling for the complete overthrow of French imperialism, an end to Vietnamese feudalism, the confiscation of land from the colonisers and big landowners and its distribution to poor peasants, an eight-hour working day, universal education, and equality between men and women – a simple, profound revolutionary programme giving voice to the deepest aspirations of ordinary Vietnamese people. This is the party, later renamed as the Communist Party of Vietnam, that went on to lead the Vietnamese masses in the overthrow of imperialism and the pursuit of socialism, a task it remains engaged in to this day.

In the following two months, acting under the instructions of the Comintern, Ho found time to preside over the establishment of the Siamese Communist Party and attend a meeting establishing the Malayan Communist Party. Meanwhile, the influence of the ICP was rapidly expanding, along with the militancy and self-confidence of the Vietnamese workers and peasants. Strikes were breaking out in all parts of the country, and in 1931 a series of insurrections led to the creation of the Nghe Tinh soviet in two provinces of central Vietnam, Nghe An and Ha Tinh (more details of this period can be found in the article Fight to Win: How the Vietnamese people rose up and defeated imperialism ).As Ho later wrote, “although the movement was drowned by the imperialists in a sea of blood, it testified to the heroism and revolutionary power of the Vietnamese working masses. In spite of its failure, it forged the forces which were to ensure the triumph of the August Revolution.”

Ho continued in his role as the ICP’s chief strategist until he was arrested and imprisoned in Kowloon by the British colonial authorities – reporting to Ramsey MacDonald’s Labour government.

After a year and a half in prison, having successfully been defended by the British lawyer Denis Pritt (who later earned the honour of being expelled from the Labour Party on account of his pro-Soviet views), Ho was able to avoid extradition to France and to make his way instead back to the Soviet Union. In Moscow he was put in charge of the Vietnamese section of the Far Eastern Bureau of the Comintern, and he also enrolled in a course at the Lenin University. Nguyen Khanh Toan, who would later serve in various high-level governmental positions in Vietnam from 1945 until the 1980s, was one of the 150-ish Vietnamese students under Ho Chi Minh’s supervision at the time, and he gives a moving description of Ho’s interaction with the students:

” While studying at the Lenin University he kept in very close touch with the Vietnamese group. In the evenings he often came to talk to them about his experiences in revolutionary action, putting heavy emphasis on revolutionary morals, especially the sense of solidarity. Among the younger students there sometimes arose squabbles of mostly a personal character, and he had to arbitrate them. What he sought to combat among them was arrogance, egoism, indiscipline; he wanted them to be united and put the interest of the revolution above everything else. He often said to them: ‘If even this little group of ours cannot live in harmony and solidarity, how could we hope, once back in the country, to unite the people and rally the masses against the colonialists in order to save the nation?” (Reminiscences of Ho Chi Minh)

Leading Vietnam to victory

After a few relatively peaceful years studying and organising in the Soviet Union, Ho returned in 1938 to China, where he was appointed as a political commissar, working to educate troops at the Whampao Academy. In China, Ho was reunited with his closest allies, including Vo Nguyen Giap, Pham Van Dong and Truong Chinh. In 1940 they decided that the time was ripe to infiltrate themselves back into Vietnam with a view to organising a nationwide insurrection. In early February 1941, they made the short but difficult journey across the border from China into the northernmost part of Vietnam, establishing themselves in a cave near the village of Pac Bo, a small village in Cao Bang province, just the other side of the Chinese border. Duiker writes:

” With the aid of a local sympathizer, the group established their accommodations in a cave known to the locals as Coc Bo (the Source) and situated behind a rock in the side of one of the local cliffs. About 140 feet below the mouth of the cave was a stream that Nguyen Ai Quoc named for his hero Lenin. Overlooking the site was a massive outgrowth that he dubbed Karl Marx Peak. From the cave, a secret path wound straight to the Chinese border, less than half a mile away. In later years, Nguyen Ai Quoc and his colleagues would remember their days at Pac Bo as among the most memorable in their lives. Yet conditions were harsh. They slept on a mat of branches, leaving them with bruised backs in the morning. The cave itself was cold and damp, so the occupants kept a small fire going all night. As was his habit, Nguyen Ai Quoc rose early, bathed in the stream, did his morning exercises, and then went to work on a rock at the edge of Lenin Stream. As always, he spent much of his time editing, this time working on the Party’s local newspaper, Viet Nam Doc Lap (Independent Vietnam), which was produced on a stone lithograph. Meals consisted of rice mixed with minced meat or with fish from the stream. In the evening, the group would gather at the edge of the cave, where Nguyen Ai Quoc lectured to his colleagues on world history and modern revolutions.”

Later on, they were often forced to forage for food. It must have been extraordinarily tough for the veteran revolutionary, by now in his fifties, to endure the life of a mountain guerrilla. However, he did so without complaining. “When spirits flagged or enthusiasm grew to excess, he counseled his comrades: ‘Patience, calmness, and vigilance, those are the things that a revolutionary must never forget.’”

The key event from this period is the formation of the Viet Minh front on 19 May 1941, in the cave at Pac Bo. The Viet Minh was formed as an anti-imperialist front to unite all forces, communist and nationalist, in a single fighting organisation able to rid the country of colonial occupiers. In the space of a few years, its membership grew to over half a million (out of a total population of less then 25 million). A leaflet announcing the Viet Minh’s existence describes the broad class basis of the front, pointing out that, in the conditions then prevailing, maximum unity must be forged in order to defeat the French:

” The problem of class struggle will continue to exist. But at the present time, the nation has prime importance, and all demands that are of benefit to a specific class but are harmful to the national interest must be subordinated to the survival of the nation. At this moment, if we do not resolve the problem of national liberation, and do not demand independence and freedom for the entire people, then not only will the entire people of our nation continue to live the life of beasts, but also the particular interests of individual social classes will not be achieved for thousands of years.”

In August 1942, Ho made his way back over the border to China in a bid to shore up international support for the Vietnamese revolution. He didn’t get very far before he was captured by the Chinese authorities and placed in prison under suspicion of being a spy. After enduring horrific conditions for over a year (during which time he contracted tuberculosis), he was finally released in September 1943 on the condition that he coordinate with the Kuomintang.

Meanwhile events were proceeding at a fast pace inside Vietnam. A pamphlet distributed in early 1944 shows that the Viet Minh leadership had an extremely clear-sighted understanding of the local and international situation: “Zero hour is near. Germany is almost beaten, and her defeat will lead to Japan’s. Then the Americans and the Chinese will move into Indochina while the Gaullists rise against the Japanese. The latter may well topple the French fascists prior to this, and set up a military government… Indochina will be reduced to anarchy. We shall not even need to seize power, for there will be no power… Our impending uprising will be carried out in highly favourable conditions, without parallel in the history of our country. The occasion being propitious and the factors favourable, it would be unforgivable not to take advantage of them. It would be a crime against the history of our country.”(cited in Jean Lacouture, ‘Ho Chi Minh’)

With precisely such a power vacuum starting to emerge in late 1944, the Viet Minh started to expand its base outwards from Cao Bang, with units under the command of General Giap pushing further and further south, creating extensive liberated areas.

With the Japanese surrender of 15 August 1945, Viet Minh forces launched the August Revolution. On 17 August, Ho read out his appeal to the people of Vietnam to take power:

” The decisive hour in the destiny of our people has struck. Let us stand up with all our strength to liberate ourselves! Many oppressed peoples the world over are vying with one another in the march to win back their independence. We cannot allow ourselves to lag behind. Forward! Forward! Under the banner of the Viet Minh Front, move forward courageously!”

Two days later Hanoi was liberated, and within a few days the Viet Minh had established power throughout the country. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam was born. On 2 September, Ho Chi Minh read out the Declaration of Independence in the Ba Dinh square in Hanoi, to a crowd of over half a million ecstatic Vietnamese.

Immediately, the new government, led by President Ho Chi Minh, started to deal with the most pressing problems: eradicating famine, eradicating illiteracy, redistributing land, setting up a stable government, and organising local militia units across the country to defend the revolution from the combination of French, US, British and Chinese forces that would almost certainly seek to reverse it.

Just over a year later, in spite of the generous concessions offered by Ho’s negotiating team, France went to war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, in a bid to maintain its domination of the region. The Viet Minh returned to guerrilla warfare, and Vietnam’s president and the rest of the leadership returned to the northeastern mountains. Duiker writes: “With his return to the Viet Bac in late December 1946, Ho Chi Minh resumed the life that had appeared to come to an end with his election as president during the August Revolution of 1945. He arrived at the old base area with an entourage of eight men, comprising his personal bodyguard and those responsible for liaison with other units and for food preparation. The group erected a long hut built of bamboo and thatch that was divided into two rooms… To guard against wild animals, they obtained a shepherd dog, but it was soon killed and eaten by a tiger. Ho and his companions led a simple life. Their meals consisted of a little rice garnished with sautéed wild vegetables. On occasion, they were able to supplement their meager fare with small chunks of salted meat, thinly sliced and served with peppers. Ho laughingly described it as ‘conserves du Vietminh.’ Sometimes food was short, and all suffered from hunger… During the day, Ho worked on the ground floor, but at night he slept on the upper floor as protection against wild beasts and the humidity. His bedding consisted solely of a mosquito net and his clothing. When the group was compelled to move (by the end of the decade, Ho would live in at least twenty different houses as he continually escaped detection by the French), they were able to pack up and leave in minutes. Ho carried a few books and documents in a small bag, while his companions took charge of his typewriter.”

Duiker adds some fascinating detail as to Ho’s role during the war: “In the liberated zone, Ho Chi Minh was highly visible, acting not only as a war strategist, but also as chief recruiter and cheerleader for the revolutionary cause. In February 1952, a released French POW reported that Ho was seen everywhere at the front, in the villages, in the rice fields, and at local cadre meetings. Dressed like a simple peasant, he moved tirelessly among his followers, cajoling his audiences and encouraging them to sacrifice all for the common objective. Although living conditions in the liberated zone were probably somewhat better than they had been during the final months of World War II, French bombing raids on the area were frequent and Ho continued to change his residence every three to five days to avoid detection or capture. Although he was now over sixty, Ho was still capable of walking thirty miles a day, a pack on his back, over twisting mountain trails. He arose early to do exercises. After the workday was over, he played volleyball or swam and read in the evening.”

From this point, the story of Ho Chi Minh’s life becomes one and the same as the history of the Vietnamese victory over France (1954), the building of socialism in the north, the support for guerrilla struggle in the south, and the era-defining war against US imperialism. More on all of this can be found in my recent article on the 40th anniversary of the liberation of Saigon.

Ho Chi Minh died on 2 September 1969, at the age of 79. Although he had played a reduced role in the last few years of his life (due to ill health), he remained a major contributor, particularly in negotiations and foreign relations. Eulogies flooded in for this outstanding leader of the global anti-imperialist movement – according to Duiker, the Hanoi authorities received more than 22,000 messages from 121 countries offering condolences to the Vietnamese people.

Ho’s legacy is as powerful and as relevant today as it ever was; his name remains synonymous with determined struggle for freedom, with the spirit of unity, with heroism, selflessness, perseverance, moral uprightness, and with the global fight against imperialism and for socialism. He was unquestionably one of the greatest leaders in the history of the anti-imperialist and communist movement.

Quotes

Unity

Unity is an extremely precious tradition of our Party and people. All comrades, from the Central Committee down to the cells, must preserve the unity and oneness of mind in the Party as the apple of their eye. (Quoted by former Communist Party General Secretary, Le Kha Phieu in ‘Party building and unification – biggest challenge’, Voice of Vietnam online, 1 September 2014).

Without this unity we would be like an orchestra in which the drums play one way and the horns another. It would not be possible for us to lead the masses and make revolution (On Revolutionary Morality, 1958)

Our people must learn the word ‘unity’: unity of spirit, unity of effort, unity of hearts, unity of action. (quoted in Duiker)

The war against colonialism

We, a small nation, will have earned the signal honour of defeating, through heroic struggle, two big imperialisms – the French and the American – and of making a worthy contribution to the world national liberation movement. (Last Testament, 1969)

At Dien Bien Phu], for the first time in history a small colony had defeated a big colonial power. This was a victory not only of our people but also of the world forces of peace, democracy and socialism.(Thirty years of activity of the Party, 1960)

The Vietnamese people are waging the greatest war of resistance in their history. For the sake of the independence and freedom of the Fatherland, in the interest of the socialist camp, the oppressed peoples and progressive mankind, we are fighting and defeating the most cruel enemy of humanity. In our land a fierce struggle is taking place between justice and injustice, between civilisation and barbarity. The people of the brother socialist countries and progressive people all over the world are turning their eyes toward Viet Nam and warmly congratulating our compatriots and fighters. (Appeal on the occasion of July 20, 1968)

Our people are very heroic. Our line is most correct. We have justice on our side. We are inspired by an unbending will and determination to fight and win. We have the invincible force of the unity of our entire people and enjoy the sympathy and support of all progressive mankind. The US imperialists are sure to be defeated! Our people are sure to be victorious! Compatriots and fighters in the whole country, march forward! (ibid)

Our resistance is by all the people and is in turn a people’s war. Thirty-one million compatriots in the two regions, irrespective of sex and age, must be thirty-one million heroic combatants to fight the US for national salvation … Unity, unity, great unity; success, success, great success. (Ho Chi Minh, cited in ‘The anti-US war for national salvation – a great victory of ability and intelligence’ by General Vo Nguyen Giap, 2005)

Johnson and his clique should realize this: they may bring in half a million, a million or even more troops to step up their war of aggression in South Vietnam. They may use thousands of aircraft for intensified attacks against North Vietnam. But never will they be able to break the iron will of the heroic Vietnamese people, their determination to fight against American aggression, for national salvation. The more truculent they grow, the more serious their crimes. They war may last five, ten, twenty or more years; Hanoi, Haiphong and other cities and enterprises may be destroyed; but the Vietnamese people will not be intimidated! Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom. Once victory is won, our people will rebuild their country and make it even more prosperous and beautiful. (Appeal to compatriots and fighters throughout the country, 17 July 1966).

Our people are living a most glorious period of history. Our country has the great honour of being an outpost of the socialist camp and of the world’s peoples fighting against imperialism, colonialism and neocolonialism. Our people are fighting and making sacrifices not only for their own freedom and independence, but also for the freedom and independence of other peoples and for world peace. On the battlefront against the US imperialist aggressors, our people’s task is very heavy but also very glorious. (Address to the Second Session of the Third National Assembly of the DRVN, April 10, 1965).

You must know of our resolution. Not even your nuclear weapons would force us to surrender after so long and violent a struggle for the independence of our country (quoted by Alden Whitman, ‘Ho Chi Minh was noted for success in blending nationalism and communism’, New York Times, 4 September 1969).

US imperialism is the main enemy of world peace, consequently we must concentrate our forces against it. (Report to the 6th Plenum of the VietNam Workers’ Party Central Committee (July 15, 1954).

The Vietnamese people’s future is as bright as the sun in spring. Overjoyed at the radiance of the sun in spring, we shall struggle for the splendid future of Viet Nam, for the future of democracy, world peace and socialism. We triumph at the present time, we shall triumph in the future, because our path is enlightened by the great Marxist-Leninist doctrine (The imperialist aggressors can never enslave the heroic Vietnamese people, 1952).

Unity between the socialist and anti-imperialist movements

Lenin laid the basis for a new and truly revolutionary era in the colonies. He was the first to denounce resolutely all the prejudices which still persisted in the minds of many European and American revolutionaries… He was the first to realise and assess the full importance of drawing the colonial peoples into the revolutionary movement. He was the first to point out that, without the participation of the colonial peoples, the socialist revolution could not come about… Lenin’s strategy on this question has been applied by communist parties all over the world, and has won over the best and most active elements in the colonies to the communist movement. (Lenin and the colonial peoples, 1925)

Anti-war movement

To the American people who are courageously opposing the aggressive war waged by the US government, I convey my greetings on behalf of the Vietnamese people. Let them intensify their opposition to the US government’s aggressive war in Vietnam so as to prevent their sons and brothers from being use as cannon-fodder for the private interests of their oppressors and exploiters. Officers and soldiers of the United States and its satellites, who have been driven into this criminal war, listen to reason! There is no enmity between you and the Vietnamese people. The US imperialists are forcing you to serve as cannon-fodder and die in their place. They are doomed to defeat. Demand your repatriation so that you can be re-united with your parents, wives and children! The Vietnamese people will support your struggle (Appeal on the occasion of July 20, 1965).

Revolutionary morality

Ours is a party in power. Each Party member, each cadre must be deeply imbued with revolutionary morality, and show industry, thrift, integrity, uprightness, total dedication to the public interest and complete selflessness. Our Party should preserve absolute purity and prove worthy of its role as the leader and very loyal servant of the people. (Ho Chi Minh’s Testament, 10 May 1969).)

To make the revolution, to transform the old society into a new one is a very glorious, but also extremely heavy task, a complex, protracted and hard struggle. Only a strong man can travel a long distance with a heavy load on his back. A revolutionary must have a solid foundation of revolutionary morality in order to fulfil his glorious revolutionary task. (On revolutionary morality, 1958).

Individualism is something very deceitful and perfidious, it skilfully induces one to backslide. And everybody knows that it is easier to backslide than to progress. That is why it is very dangerous. To shake off the bad vestiges of the old society and to cultivate revolutionary virtues, we must study hard, and educate and reform ourselves in order to progress continuously. Otherwise we shall retrogress and lag behind, and shall eventually be rejected by the forward-moving society (ibid).

Separated from the Party and the class, no individual, however talented, can achieve anything (ibid).

Revolutionary morality does not fall from the sky. It is developed and consolidated through persevering daily struggle and effort. Like jade, the more it is polished the more it shines. Like gold, it grows ever purer as it goes into the melting pot. What can be a greater source of happiness and glory than to cultivate one’s revolutionary morality so as to bring a worthy contribution to the building of socialism and the liberation of mankind! (ibid).

No system equals socialism and communism in showing respect for man, paying due attention to his legitimate individual interests and ensuring that they be satisfied. In a society ruled by the exploiting class only the individual interests of a few people belonging to this class are met, whereas those of the toiling masses are trampled underfoot. But in the socialist and communist systems, of which the labouring people are the masters, each man is a part of the collective, plays a definite role in it and contributes his part to society. That is why the interests of the individual lies within those of the collective and are part of them. Only when the latter are secured can the former be satisfied (ibid).

Revolutionary ideology

At first, patriotism, not yet communism, led me to have confidence in Lenin, in the Third International. Step by step, along the struggle, by studying Marxism-Leninism parallel with participation in practical activities, I gradually came upon the fact that only socialism and communism can liberate the oppressed nations and the working people throughout the world from slavery ( The path which led me to Leninism, April 1960).

All Party members should strive to study Marxism-Leninism, strengthen their proletarian class stand, grasp the laws of development of the Vietnamese revolution, elevate their revolutionary morality, vigorously combat individualism, foster proletarian collectivism, be industrious and thrifty in the work for national construction, build close contacts with the labouring masses, and struggle whole-heartedly for the interests of the revolution and the Fatherland (ibid.).

Cultural imperialism

In the areas still under his temporary occupation, the enemy strives to disseminate a depraved culture and hooli-ganism in order to poison our people, especially our youth. He seeks to use religions to divide our people (Ho Chi Minh, Selected Writings, Foreign Langu-ages Publishing House, 1977, p.160).

The split in the world communist movement

Being a man who has devoted his whole life to the revolution, the more proud I am of the growth of the international communist and workers’ movement, the more pained I am by the current discord among the fraternal Parties. I hope that our Party will do its best to contribute effectively to the restoration of unity among the fraternal Parties on the basis of Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism, in a way which conforms to both reason and sentiment. I am firmly confident that the fraternal Parties and countries will have to unite again ( Ho Chi Minh’s Testament, 10 May 1969).

We fully believe that the differences in the international communist movement will be resolved. Marxism-Leninism will certainly be victorious, the socialist camp and the international communist movement will grow ever more united and powerful. By giving a strong impetus to the revolutionary struggle of the working class and the world’s people they will win ever greater victories for peace, national independence, democracy and socialism. ( Report at the Special Political Conference, 27 March 1964).

Guerrilla warfare

What matters the most is that our armed forces, be they regulars, regional or guerrillas, must hold fast to the people; divorce from the latter will surely lead to defeat. To cling to the people means to win their hearts, gain their confidence and affection. This will allow us to overcome any difficulty and achieve sure success. (Instructions given at a Conference on Guerrilla Warfare, July 1952).

The aim of guerrilla warfare is not to wage large-scale battles and win big victories, but to nibble at the enemy, harass him in such a way that he can neither eat nor sleep in peace, to give him no respite, to wear him out physically and mentally, and finally to annihilate him. Wherever he goes, he should be attacked by our guerrillas, stumble on land mines or be greeted by sniper fire ( ibid.).

It will be a war between an elephant and a tiger. If the tiger ever stands still the elephant will crush him with his mighty tusks. But the tiger does not stand still. He lurks in the jungle by day and emerges by night. He will leap upon the back of the elephant, tearing huge chunks from his hide, and then he will leap back into the dark jungle. And slowly the elephant will bleed to death. That will be the war of Indochina (quoted by Duiker, op.cit.)

Secrecy, always secrecy. Let the enemy think you’re to the west when you are in the east. Attack by surprise and retreat before the enemy can respond… Stealth, continual stealth. Never attack except by surprise. Retire before the enemy has a chance to strike back. (quoted by Duiker, op.cit.)

Remember that the storm is a good opportunity for the pine and the cypress to show their strength and their stability.( Quoted by Olivia Kroth, ‘Russia’s return to Vietnam’, 4 March 2013, English Pra vda online).

Racism and the national question

It is well-known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family. It is well-known that the spread of capitalism and the discovery of the New World had as an immediate result the rebirth of slavery. What everyone does not perhaps know is that after sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching… Thanks to the slave traders, the Ku Klux Klan and other secret societies, the illegal and barbarous practice of lynching is spreading and continuing widely in the states of the American Union. It has become more inhuman since the emancipation of the Blacks, and is especially directed at the latter. The Negroes, having learned during the war that they are a force if united, are no longer allowing their kinsmen to be beaten or murdered with impunity (Report to the Fifth Congress of the Communist International, July 1924 ).

All the martyrs of the working class, those in Lausanne like those in Paris, those in Le Havre like those in Martinique, are victims of the same murderer: international capitalism. And it is always in belief in the liberation of their oppressed brothers, without discrimination as to race or country, that the souls of these martyrs will find supreme consolation. (Oppression hits all races, 17 August 1923).

Our country is a united multi-national country. All nationalities living on Vietnamese territory are equal in rights and duties. All the nationalities in our country are fraternally bound together; they share a common territory and in the course of our long history have worked and fought side by side in order to build our beautiful Fatherland ( Report on the draft amended Constitution, 18 December, 1959).

Imperialism and feudalism deliberately sought to undermine the solidarity and equality between the nationalities and to sow discord among them and carried out a ‘divide-and-rule’ policy. Our Party and Government have constantly called on the nationalities to forget all enmities caused by imperialism and feudalism and to unite closely on the basis of equality in rights and duties. The minority nationalities have, side by side with their brothers of the majority nationality, fought against their common enemies, and brought the August Revolution and the war of resistance to success. Since the restoration of peace, our State has helped the brotherly nationalities to achieve further progress in the economic, cultural and social fields (ibid).

The October Revolution and the socialist camp

Like the shining sun, the October Revo-lution illuminated the five continents, and awakened millions and millions of oppressed and exploited people. In human history, there had never been a revolution with such great and profound significance (The great October Revolution opened the road of liberation to all peoples, October 1967).

Our Party has matured and developed in the favourable international conditions created by the victory of the Russian Socialist October Revolution. All achievements of our Party and people are inseparable from the fraternal support of the Soviet Union, People’s China and the other socialist countries, the international Communist and workers’ movement and the national-liberation movement and the peace movement in the world. If we have been able to surmount all difficulties and lead our working class and people to the present glorious victories this is because the Party has coordinated the revolutionary movement in our country with the revo-lutionary movement of the world working class and the oppressed peoples (Thirty years of activity of the Party, 1960).

After nearly half a century of struggle, the imperialist and feudal domination was not yet overthrown and our country was not yet independent. It was then that the Russian October Revolution broke out and won glorious victory. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was founded. The colonial system of imperialism began to collapse. The Soviet Union brought to the oppressed peoples a model of equal relationships between the nations. The oppressed peoples of the world saw that only by relying on socialist revolution and following the line of the working class was it possible to overthrow the imperialists, win back complete national independence and realize genuine equality among the nations. The Russian October Revolution welded the socialist revolutionary movement and the revolutionary movement for national liberation into an anti-imperialist front. ( Report on the draft amended Constitution,op.cit.).

In the eyes of the peoples of the east, Lenin was not only a leader, a commander. He irresistibly attracted our hearts. Our respect for him was close to filial piety, one of the fundamental virtues in our country. For us, the victims of ill-treatment and humiliation, Lenin was the embodiment of human fraternity.” (cited by Yevgeny Kobelev – Ho Chi Minh)

Lenin is dead! This news struck people like a bolt from the blue. It spread to every corner of the fertile plains of Africa and the green fields of Asia. It is true that the black or yellow people do not yet know clearly who Lenin is or where Russia is… But all of them, from the Vietnamese peasants to the hunters in the Dahomey forests, have secretly learnt that in a faraway corner of the earth there is a nation that has succeeded in overthrowing its exploiters… They have also heard that that country is Russia, that there are courageous people there, and that the most courageous of them all was Lenin (ibid).

Building socialism and educating the masses

The present society in the North is one of working people who are collective masters of the country and uphold the spirit of self reliance, industry and thrift in order to build socialism and a new life for themselves and for all generations to come. The present society in the North is a great family formed by all strata of the population, all fraternal nationalities, closely united and helping each other, sharing weal and woe and working for the common interests of the Fatherland. Our regime is a new regime; our people are cultivating new ethics; the socialist ethics of working people: “one for all and all for one” (Report at the Special Political Conference, op.cit.).

In simple terms, the aim of socialism is to free the working people from poverty, provide them with employment, make them happy and prosperous. (Thirty years of activity of the Party, 1960).

To defeat the imperialists and feudalists is relatively easy, but to do away with poverty and backwardness is much more difficult (quoted by Pham Van Dong – a man, a nation, an age and a cause).

To reap a return in ten years, plant trees. To reap a return in 100, cultivate the people.

Formerly, when they ruled over our country, the French colonialists carried out a policy of obscurantism. They limited the number of schools; they did not want us to get an education so that they could deceive and exploit us all the more easily. Ninety-five per cent of the total population received no schooling, which means that nearly all Vietnamese were illiterate. How could we have progressed in such conditions? Now that we have won back independence, one of the most urgent tasks at present is to raise the people’s cultural level. Every one of you must know his rights and duties. He must possess knowledge so as to be able to participate in the building of the country. First of all he must learn to read and write. Let the literates teach the illiterates; let them take part in mass education. Let the illiterates study hard. The husband will teach his wife, the elder brother his junior, the children their parents, the master his servants; the rich will open classes for illiterates in their own houses. The women should study even harder for up to now many obstacles have stood in their way. It is high time now for them to catch up with the men and be worthy of their status of citizens with full electoral rights. I hope that young people of both sexes will eagerly participate in this work (Appeal to fight illiteracy, October 1945).

Workers and peasants have a lot of work to do. If the method of teaching is not suitable to the learners, to their work and mode of life, if we expect classes provided with tables and benches, we cannot be successful. The organization of teaching should be in accordance with the living conditions of the learners, then the movement will last and bear good results. Our compatriots are still poor and cannot afford paper and pens, therefore a small pocket exercise-book is enough for each person. Reading and writing exercises can be done anywhere, using charcoal, the ground or banana leaves as pens and paper. Clandestine cadres had to teach and make one person literate every three months. At that time, there was no assistance from the Government, no Ministry, or department in charge of educational problems, but in such precarious conditions, the movement kept developing, like oil spreading, the literate teaching the illiterate. (Instructions given at the conference reviewing the mass education in the first half of 1956, 16 July 1956).

The worker-peasant alliance

The victory of the proletarian revolution is impossible in rural and semirural countries if the revolutionary proletariat is not actively supported by the mass of the peasant population…. In China, in India, in Latin America, in many European countries (Balkan countries, Rumania, Poland, Italy, France, Spain, etc.) the decisive ally of the proletariat in the revolution will be the peasant population. Only if the revolutionary wave sets in motion the rural masses under the leadership of the proletariat, will the revolution be able to triumph. Hence the exceptional importance of Party agitation in the countryside. (quoted by Duiker, op.cit.)

Revolutionary art

Literature and art are also a fighting front. You are fighters on this front. Like other fighters, you combatants on the artistic front have definite responsibilities: to serve the Resistance, the Fatherland and the people, first and foremost the workers, peasants and soldiers. To fulfil your tasks, you must have a firm political stand and a sound ideology; in short you must place the interests of the Resistance, the Fatherland and the people above all… Some of you may think: President Ho is trying to link art to politics. That is right. Culture and art, like all other activities, cannot stand aloof from economics and politics, but must be included in them (To the artists on the occasion of the 1951 painting exhibition, December 10, 1951) .

Compromise

Lenin said that one should make a compromise even with bandits if it was advantageous to the revolution. We needed peace to build our country, and therefore we forced ourselves to make concessions in order to maintain peace. Although the French colonialists broke their word and unleashed war, nearly one year of temporary peace had given us time to build up our basic forces (Political Report at the Second National Congress of the Viet Nam Workers’ Party, February 1951).

Manure is dirty; but if it’s good for the rice plants, would you refuse to use it? (quoted in Duiker, op.cit.)

Some people, intoxicated with our repeated victories, want to fight on at all costs, to a finish; they see only the trees, not the whole forest; with their attention focused on the withdrawal of the French they fail to detect their schemes; they see the French but not the Americans; they are partial to military action and make light of diplomacy. They are unaware that we are struggling in international conferences as well as on the battlefields in order to attain our goal. They will oppose the new slogans, which they deem to be rightist manifestations and to imply too many concessions. They set forth excessive conditions unacceptable to the enemy. They want quick results, unaware that the struggle for peace is a hard and complex one. Leftist deviation will cause one to be isolated, alienated from one’s own people and those of the world, and suffer setbacks. Rightist deviation will lead to pessimism, inaction and unprincipled concessions. It causes one to lack confidence in the people’s strength and to blunt their combative spirit; to lose the power to endure hardships and to aspire only to a quiet and easy life. Leftist and rightist tendencies are both wrong. They will be exploited by the enemy; they will benefit them and harm us (Report to the 6th Plenum of the Viet Nam Workers’ Party Central Committee, July 15, 1954) .