Nations short of vaccine should get first doses to curb the pandemic, researchers say.

Israel has announced plans to begin giving booster shots to older adults next week, in the hope of increasing their protection against COVID-19 — and a number of other wealthy countries are considering the same. But global-health researchers warn that this strategy could set back efforts to end the pandemic. Each booster, they say, represents a vaccine dose that could instead go to low- and middle-income countries, where most citizens have no protection at all, and where dangerous coronavirus variants could emerge as cases surge.

Data do not yet show that extra doses are needed to save lives, researchers say, except perhaps for people with compromised immune systems, who might fail to generate much of an antibody response to the initial COVID-19 shots.COVID vaccines to reach poorest countries in 2023 — despite recent pledges

An internal analysis from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that if the 11 rich countries that are either rolling out boosters or considering it this year were to give the shots to everyone over 50 years old, they would use up roughly 440 million doses of the global supply. If all high-income and upper-middle-income nations were to do the same, the estimate doubles.

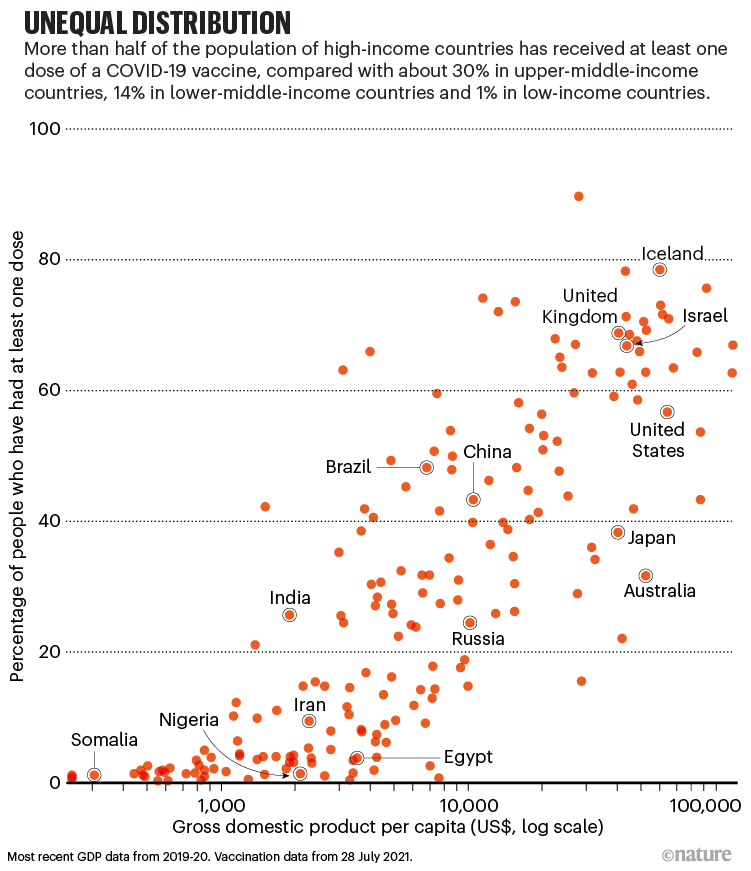

The WHO maintains that these shots would be more useful for curbing the pandemic if they were sent to low- and lower-middle-income countries, where more than 85% of people — some 3.5 billion — haven’t had a single jab. “The priority now must be to vaccinate those who have received no doses,” said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at a briefing on 12 July.

All of the COVID-19 vaccines authorized by most high-income countries reduce a person’s risk of hospitalization and death by more than 90%. Scientists don’t yet know how much more a booster — typically an extra jab of an mRNA-based vaccine on top of the standard doses — would protect the average person, although data are beginning to trickle in. The effects of not receiving any vaccine are more certain. On the African continent, where only 2% of people have been vaccinated, COVID-19 rates are escalating, with fatality rates higher than the global average.

Without vaccines, researchers say, the best tools for slowing the spread of infections are interventions such as closing businesses and schools, which can have devastating economic consequences. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that 95 million people were pushed into extreme poverty during the pandemic last year, and numbers are rising. On 27 July, the organization reported a widening wealth gap between rich countries and the rest of the world.

What’s more, evolutionary biologists say that countries with low vaccination coverage are ripe for the emergence of further dangerous variants of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. “Right now, our destiny relies on distributing vaccines so that continued transmission doesn’t occur,” says Nahid Bhadelia, director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases Policy and Research at Boston University in Massachusetts. “We don’t want to be chasing our tail in terms of new variants.”

Contemplating boosters

Israel is not alone in considering boosters for older people. Spurred partly by data1 suggesting that antibody levels wane over time, the United Kingdom has drawn up plans — but not given final approval — for a booster programme to begin in September for older people, front-line health workers and others at high risk of COVID-19.

In early July, the US government decided against boosters for the time being, but said it was prepared to roll them out when science demonstrated a need. Last week, the United States purchased another 200 million mRNA vaccines made by pharmaceutical firm Pfizer, based in New York City, and biotechnology firm BioNTech, based in Mainz, Germany, that might be used for booster shots if studies show they are necessary.

The United States and other nations are hesitating because current COVID-19 vaccines still protect people, despite uncertainty about how long their effects will last. This week, a not-yet peer-reviewed report from Pfizer2 found that its vaccine’s efficacy rate against symptomatic COVID-19 fell from 96% for the two months after the usual two doses to 84% six months later. But its efficacy against severe disease remained high, at 97%.

Decisions on boosters might also be influenced by the rise of the Delta variant in many parts of the world, and the possibility that vaccinated people could transmit it to others if they become infected. In theory, further reducing the risk of infection for vaccinated people diminishes the possibility of Delta’s spread. The variant was first reported in India in late 2020, but remained relatively rare until March, when a surge occurred. Few people in the country had been vaccinated at the time, allowing the virus to spread in India and beyond.

A similar scenario might play out again in an area with low vaccination coverage and a lot of COVID-19. A new variant could arise that is more transmissible or deadlier than Delta, or that allows the virus to escape — at least to some extent — immunity gained from vaccination or a previous infection, says Katrina Lythgoe, an evolutionary biologist at the Big Data Institute at the University of Oxford, UK. “Making predictions is really hard,” she adds, but it’s safe to say that in places with more infections, there are more viruses replicating and therefore more opportunities for variants to evolve.

The sting of inequity

If there were enough vaccines for every adult in the world, third doses for those in rich countries wouldn’t appal so many researchers. But disparities are growing. A July report from KFF, a health-policy organization based in San Francisco, California, finds that low-income countries won’t achieve substantial levels of protection until at least 2023, at current vaccination rates. Almost all of the roughly 3.2 billion mRNA vaccine doses expected this year from manufacturers Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, have been purchased by the United States and Europe, according to the London-based analytics company Airfinity. Although some of those will be donated to countries in need, the KFF report suggests that they will be insufficient. The pace of vaccination in low-income countries needs to increase 19-fold to inoculate 40% of those nations’ populations by the end of the year, the report says.What it will take to vaccinate the world against COVID-19

This modest vaccination target of 40% is endorsed by the WHO, the World Bank and the IMF as a threshold that would significantly reduce deaths and allow economies to begin recovery. But because it looks increasingly out of reach, the IMF has revised its economic forecasts for 2021, downgrading projections for developing and emerging economies. It warns that highly infectious variants could derail worldwide economic recovery and wipe US$4.5 trillion from the global gross domestic product by 2025.

Countries are justifying booster shots on the basis that their duty is to protect their residents first. Officials in Israel, where 62% of the population has been fully vaccinated, are concerned about a rise in COVID-19 infections over the past month. Eran Segal, a computer scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot and a COVID-19 consultant to the Israeli government, says that some of the rise could be due to vaccines’ protection wearing off, although other factors, such as people spending more time together unmasked, can influence infection rates. On using boosters in Israel rather than providing them to unvaccinated people elsewhere, Segal says that the country’s programme will require just over one million doses. “It’s negligible,” he says, “and the world will learn from this experience.”‘Unprecedented achievement’: who received the first billion COVID vaccinations?

For many, this reasoning does not assuage the sting of vaccine inequity. Organizations including Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, also known as Doctors Without Borders) in Geneva, Switzerland, and advocacy group Public Citizen in Washington DC have reacted to news of boosters with outrage. “Instead of solving the problem by vaccinating the world and cutting off new variants, rich countries seem prepared to fork over more money for boosters, and live in a state of endless fear,” says Achal Prabhala, a public-health activist at the non-profit AccessIBSA project in Bengaluru, India.

For Leena Menghaney, the South Asia regional head of the Access Campaign at MSF, this debate is personal. She was caught in a stampede for a limited supply of vaccines offered earlier this month in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most densely populated state, where the desperation was palpable. “We have always known that we were second-class citizens,” she says, “but you really feel it in that moment.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02109-1

References

- 1.Shrotri, M. et al. Lancet 398, 385–387 (2021).Article Google Scholar

- 2.Thomas, S. J. et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.28.21261159 (2021).