NOVANEWS

I have been to China several times before, but this trip, my fifth, differed from the previous ones in that I came with my wife. My schedule was fairly loose, which enabled me to see and feel China for real, not just look at facades and showpieces. Moreover, this time I was able to see China through the eyes of my wife who is no expert on China, and through socializing with people “from the street”. Two months before our trip we “swallowed” a Russian-Chinese phrase book. And because, I haven’t yet completely forgotten my Japanese, we were at least able to not lose our way in the mazes of Beijing and Shanghai.

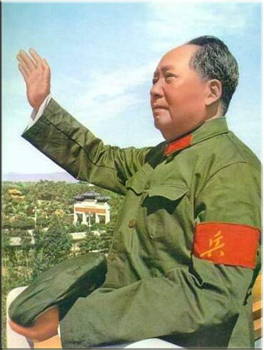

In theory, I had a fairly good knowledge of China even before the trip. Macroeconomics and politics, both domestic and foreign, is something that I study and analyse all the time. However, this latest trip enabled me to get a feel of the spirit of the Chinese, or rather, the factors that make the Chinese nation unique and enable it to make progress on the road of their reforms. Let me note right away that the leadership of the Chinese People’s Republic (CPR) and the Communist Party of China (CPC) manage the implementation of reforms very skillfully. These energetics are a good place to start.

The initial sensation of a “world-wise” man arriving in a Socialist country is that of a certain condescension or even Western cynicism about the poor Chinese who have no notion of the world outside of China. When we were leaving, our parting feeling was the certainty that they don’t really need to know. The mass enthusiasm of the country’s entire population is initially amusing to our snobbish sensitivities. The Westerner is used to people’s false smiles over their deeply hidden internal depression. God forbid that you let your true feelings show – you must always flash the “cheese” smile, or else you won’t find employment, won’t have money.

Backyard poverty is your lot. In China the joyous, energetic faces, the boldness of body and spirit at first are touching, and eventually earn your admiration. This thrust to a better future existed in Soviet Russia in the 1930s, when the people built giant factories, power stations, railroads, etc.

The streets of Beijing and Shanghai merit special attention, for they are the blood arteries of the country. The traffic there is practically impossible to comprehend, it’s only possible to sense the general flow of the entire city. The streets remind one of the whole country’s progress toward her goal: everything here moves together, maintaining the sense of the neighbor’s shoulder, never bumping or colliding with others. In a whole month we saw no traffic accidents. This is all the more amazing since the people and cars often move opposite to the indicated traffic direction. This tableau needs to be visualized: the multitude of cars, the even greater multitude of bicycles and rickshaws, the millions of pedestrians scuttling across the road in every direction, ignoring the traffic lights. All these moving objects need only half a hint to understand each other. The secret became clearer when one journalist quoted a Chinese cabbie: “We are all bicyclists here, getting around on two wheels since childhood”. Indeed, once you take this for granted, it becomes clear why the bicyclists pass each other without bumping, brake lightly or halt instantly. (But you’ll never figure out just how they manage it).

“The enthusiasm of labor” in the streets is not just a quote from Andrei Platonov – it is a fact of life here. You see no junkies, invalids or ragamuffin beggars here. Hard work is the natural way of life for the Chinese. Perhaps that’s why the normal facial expression of concern here is healthy, and the people are human through the constant exercise of labor (to borrow a phrase from Friedrich Engels). One can’t help thinking every once-in-a-while about all the panhandlers, invalids and disturbed people on the streets of Western cities, while in China there is so much normal joy and healthy emotion in people’s faces. Okay, one may ask how do you define normal? My answer: normal is what gives hope for the better and the strength to hope, what makes the good and healthy things last, instead of crippling body and soul. Humankind would have perished a long time ago if not for those who carry this burden of “normalcy”. May Vancouverites forgive me, but my wife and I always used to shudder when we passed the intersection of Main and Hastings, beholding the shabby multitude of freaks in a compassionate wealthy country like Canada. And the difference between the sexes may not have disappeared entirely in Canada, but it is barely noticeable. And may Russians in general and Muscovites in particular forgive me, but I never encountered anywhere as monstrous a transformation of people as the one in Russia, where the “new Russians” are almost inevitably ignorant, rude and thieving, and the “old Russians” are the miserable intelligentsia, shabby and devoid of hope.

Understandably, the Communist Party of China gives the people no opportunity to get stoned on narcotics or soused with alcohol, still less to eradicate visible indicators of gender – however sarcastic you want to be about it. For the kind of people who do these things they have special living quarters in special locations, so to say. And the thought occurred to us that perhaps the Chinese authorities have the right idea. The millions upon millions of Chinese have no time to cloud their brains with dope or booze, or invent exotic kinds of entertainment for themselves. They all have a lot of work to do in their short lives. The Chinese don’t count on an afterlife, they are in general not religious at all. Their only evident religion is work and physical (energetic) health in this earthly life. That’s why they are always in such a hurry, those multitudes, as they extract China from squalor and poverty. Let me phrase my thought this way: the Chinese, for all the filth of their streets and the squalor of their dwellings, are possessed of a certain cleanliness, joy, and a drive toward better things, while in the “civilized world”, where the streets are scrubbed with soap and well-lit, and the people all flash “cheese” smiles, the sensation of humanity coming to an end is palpable.

You can tell much about a country from its television programming. Beijing has some 30 channels (only one of them Westernized), Shanghai has equally as many. In the early days of our visit we poked fun at the propaganda-style display of cheerfulness on Chinese television: cheerful artists performing very cheerful songs to the accompaniment of cheerful musicians. Women singers and readers – all in military uniform for some reason – glorify their happy lives with such enthusiasm that one may get the impression that China has no problems. The endless concerts celebrating something or other, with performers all looking like princesses, create the impression of a medium dumbed-down to the max. But the moment you switch to the Western TV channel, you are swarmed with images of monsters and endless rain. The musicians torture their instruments, what passes for thought is drenched in narcotics, the performers look like they never bathe and never cut their hair. So I had the urge to switch back to the Chinese Thumbelinas in their pretty dresses. Sound funny? Perhaps it does, but such were my feelings.

Naturally, the choice of programming for the Western TV channel was made by experts from the Communist party of China. But we have seen the world, my wife and I. We know that fine cinema and excellent musicians do exist in the West, but so does “pop culture”. Even the better movies in the West have contrived plots, design to jolt the jaded Western viewers. The violence, the monsters, the gore are needed in order to sell this madness to the viewers; selling is what it’s all about.

Chinese dwellings don’t impress a visitor, to put it mildly; the standard of living is very modest. In the older streets they still use collective outhouses. The accommodations resemble those of my native Astrakhan in the 1950s. The Chinese don’t mind the inconveniences at all, they are used to outdoor life. The Chinaman is always busy producing something and then selling it. He catches a beetle, a sparrow, a frog, a snake – anything that flies, crawls or swims – fries it and sells it. The Chinese peasant sells or trades everything he grows. People sell the products of their own labours, rather than being intermediaries. They spend no more time at home than a night’s sleep.

Many Chinese now have the opportunity to save enough money for a decent apartment with modern conveniences, but they are not really concerned with the size and furnishings of their homes. Home is just a place to sleep, and they don’t sleep long; at five in the morning the Chinese is already up, and after some Tai-chi exercises he or she is off to work – to the fields, or the factory, or the marketplace. Very little of Chinese life is spent at home.

In Beijing many streets have been turned into bazaars, where any kind of food, clothing or household items can be found. Barbers don’t rent premises – they, too, set up shop in the streets. The spectacle is amusing (to us visitors): long rows of barbers and their chairs under canopies. They use no water or soap, and there are no waiting lines for a haircut – it’s the barbers who are waiting for customers. All the cut hair piles up on the pavement; in the evening some of it is swept away, but enough is left to determine what trade was plied here in the daytime. For the elite, of course, there are magnificent salons with plumbing, catering and whatnot. In the streets you see “massage parlors” that consist of a couch with a dirty sheet thrown over it. This is where the Chinese practice their energy-enhancing massage – an interesting spectacle; the cost of the procedure is about one dollar.

The Chinese marketplace is a world in itself, with its own unwritten rules. It comes alive twice daily, with a break between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m. when it’s too hot. One day my wife went out to buy groceries and returned in some excitement, with big eyes. “What happened?” “I’m not telling, take a look for yourself tomorrow; be on the spot at 3:45 p.m.” I did so, and the spectacle was indeed unique: at 3:55 p.m. there appeared in the street out of nowhere hundreds of bicycles, strollers, wheelbarrows, bags, portable stands, carrying fruit, vegetables, meats, fish and poultry, cans, tins, slippers, caps, trinkets – a page won’t suffice to list all the items that emerge and are put on display or on the grill. In some five minutes a huge, noisy creature comes into being that hollers and steams for at least three hours. One feels as if caught in a maelstrom, from which there is no escape. The shoppers who have made their purchases mount their “sacks on wheels” and proceed calmly against or across the flow of traffic, chatting all the while.

The Chinese sense of space is different. A European person always keeps a certain distance from others, protecting his/her “personal space”. The Chinese have nothing like that – in public transit and elsewhere they can be packed so tightly that to Western eyes it looks improper. The Chinese aren’t troubled by thoughts of strangers’ bodies rubbing against them; transit is just transit. Their sense of distance is also peculiar.

I asked a passerby once: “How far is it to Tiananmen Square?” – “Not far”. “Can I walk there?” “Sure”. I walked for an hour and a half to get there; evidently that’s not far by Chinese standards.

Another case to illustrate the difference of perspectives. There was this discussion about co-operation between the Far East of Russia and the Northern provinces of China, and I said that one of the problems of the Russian Far East is the small size of its population (about 8 million), which makes people fearful of Chinese immigration. I was told then that the Northern provinces are also not too populous. Meaning their population is how big? “Only about 100 million people”, I was told.

Also notoriously different is the Chinese sense of time. In Shanghai I was supposed to read two lectures daily at Fudang University. I figured one hour per lecture, which would leave me plenty of spare time. Imagine my surprise when the organizers told me they had allotted an hour and a half for each of my “monologues”, which would be followed by question periods. The question periods lasted between 2 and 2 and a half hours, meaning that each lecture lasted up to four hours, and two lectures took up an entire workday. The curiosity of the Chinese is phenomenal.

Truly stunning is the urban might of Shanghai. It is the biggest city in the Orient (14 million people, not counting the suburbs), with a special export-oriented industrial zone. The old seawall dates from the days of British domination, but there is also the new business district with skyscrapers, one of which is the third tallest in the world at 420 meters (the Chinese maintain that it is the tallest). The high-rise towers are spaced apart, so the district is not depressing the way the stone canyons of Manhattan are. There are still some patches of traditional Chinese buildings, with ancient pagodas and gardens. Shanghai is on its way to becoming one of the major finance centers of Eastern Asia, and clearly it has the potential of becoming a center of global importance.

Beijing is more traditional; it also experiences urban transformation that manifests itself in high-rises, but it preserves much more of old China (the Imperial Palace, the Temple of Heaven, Tsing-Shang Park, etc.) Our visit was in May, at the time when Beijing was restoring old buildings and building some new ones in preparation for the 50th anniversary of the People’s Republic. We knew full well that everything was supposed to be ready by October 1 – the date of the grand celebration, but still my wife decided to put the question to one passerby, testing the man’s faith in the builders (meaning the Party): “Will they finish in time?” He failed to comprehend the question at first, but after some clarifications he responded with certainty that the answer is yes, since the decision had been made by the Communist Party. Thank god that such a country still exists, we thought.

The Chinese share the unique trait of helpfulness. In the subway I got the impression that everyone is waiting for you to voice your issue, so that everyone can start discussing the ways to resolve it. The discussion would not necessarily produce a solution, but it is involvement that matters.

The children react with astonishment to the sight of fair-haired, “tall-eyed” strangers. One tiny tot simply froze when he caught sight of us and clutched his mother. My facial features and gray hair are “something entirely different” to his eyes.

We quite enjoyed the Chinese reaction to the American bombing of the PRC embassy in Belgrade. The entire country became agitated, workers and students went to anti-American protest rallies in every city. The events of those few days appear to have set right the minds of those people in China who had been sympathetic toward Americans and harbored illusions about the possibility of long-term co-operation with USA. They became convinced that America can’t be a friend, it can only be a business partner, one deal at a time. In private conversations they kept asking me to clarify just exactly how weak had Russia become, and when she would recover sufficiently from her “reforms” so that a powerful alliance could be made with China against USA.

In those days certain tensions were felt in the Chinese people’s relations to all foreigners. Americans huddled together and kept strictly to themselves, venturing out of their buses only in bunches. My wife and I weren’t openly abused, but we did suffer many awkward experiences, like casual elbows to the ribs or backs turned suddenly to our faces. We rather liked the way the Chinese “rallied to defense”.

There was one peculiar incident with my wife, who went to buy some dumplings: the noisy vendor refused to sell anything to the white woman who had to be an American. His partner hissed at him to stop scaring away customers, but the vendor steadfastly refused to serve the damn Yankee. But as soon as my wife managed to explain that she’s Russian, the vendor became friendly. The Chinese in general like Russians much better than Europeans, Americans or Japanese (I know this from public opinion polls.)

The day before we left China, I gave an interview to foreign correspondents in Beijing. Several of them were Americans who had previously worked in Moscow. They recalled their stay in Russia without any fondness, while talking with admiration about Beijing and China in general. I wanted to know why they were in love with China all of a sudden, and they all expressed the opinion that world history is currently made in China, which makes it interesting. The American teachers that I met were also trying to extend their stay in the CPR. I was surprised to discover that they enjoy their lives there. I tried to provoke them, saying: “But there are none of the comforts here that Americans are used to” “True, but they have something here that we don’t have in the West. Everything is more humane here in China”. “But surely your reason for being here is money?” – my wife asked. “Nope, we were much better paid in America, but somehow it feels good here. The Chinese don’t need our “human rights”; they have their own rights, more humane”.

So there you have it – “Socialism with a human face”, Chinese style.

From Oleg Arin and Valentina Arina. Between Titi and Kaka. The Impressions of a Tourist…but not only (Moscow: Alliance, 2001).