NOVANEWS

The Legacy of Post WWII Political Intrigue and Espionage

by Trowbridge H. Ford

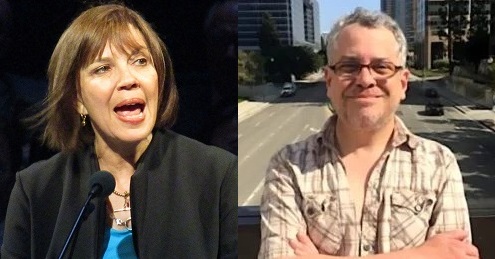

editing… Jim W. Dean

Angela Merkel

Whenever a sovereign nation is conquered by another, its inhabitants, whether they be from its elite or dregs, ultimately have a hard time adjusting to foreign occupation because they don’t know how long it will last, and what it may be replaced by.

The process is made more difficult if it seems that there is no alternative to the conquerors, especially if they appear to represent some wave of the future.

But then, there are always surprises in history, and some seemingly sure things turn out to be nothing more than delayed dead ends.

Of course, the alternative to such a course is to continue to fight the occupiers tooth and nail as there seems to be no choice about the matter, but the costs of such a course are usually devastating.

The best example of the latter is the sad fate of Poland when it was confronted by nemeses on both its borders as World War II approached. It refused to compromise with either of its threatening neighbors, and paid heavily for its choice.

The victim of yet more partitions of Poland, it still refused to accommodate with either of its invaders. Poland was the only country in Europe, when overrun, refused to recognize and cooperate with its conquerors.

Katyn Forest – Initial Excavations

In fact, it proved so obstreperous to its Soviet occupiers that they felt obliged to execute the leading officers of its military in the infamous Katyn Forest massacres for fear that they would fight with the invading Nazis when the showdown between Berlin and Moscow finally occurred.

The uncooperative Poles in the German occupied areas fared even worse as they were forced to fight back because of the Nazi liquidation of increasing numbers of its Jewish citizens, culminating in the infamous elimination of the Warsaw Ghetto.

The Poles preferred, in sum, partitions of their country aka Polonization rather than experience some kind of ‘Quisling’ rule – the sobriquet given the German occupation of Norway under the collaborationist administration of Vidkun Quisling.

Traditionally, the term Polonization had meant the political and cultural expansion of the country at the expense of its neighbors, especially Germans and Lithuanians, but now the term was used to identify the reverse process.

Ever since the failed Warsaw uprising of 1831, except for the chaos left after the collapse of World War I, the Poles had been resigned to the fate history had dictated for them, as was amply demonstrated when neither the French nor the British supplied the help they had promised when the Nzai blitzkrieg struck in 1939.

The trouble with this passive, go-it-alone strategy by the Poles when it came to improving the nation’s fortunes was that it could easily be sidetracked by others.

When the prospects of its government in exile in London started to improve, its head, General Wladyslaw Sikorski, was conveniently assassinated in Gibraltar by the Brits, it seems, in July 1943.

General Sikorski

Sikorski was a courageous leader who was willing to make hard choices, deciding better ‘Stalin than Hitler’ immediately after the Nazi forces invaded the USSR.

His vigorous cooperation with them promised some hope for the Poles in the postwar settlement – what Churchill recognized, and had MI6 apparently sabotage the plane’s controls while it was refueling, making it look like a Soviet plane, parked next to it, had been its source.

Without Sikorski, the anti-communist Poles tried to go it alone when the Soviets forces approached Warsaw, but Stalin would not hear of it.

The postwar settlement in Poland was the most repressive of all in Eastern Europe. The country itself was a convenient hodge-podge at German expense which just provided another example of Polonization.

The terms of the Yalta Conference guaranteed that its politics would be Soviet-dominated, and the consequences were the least troublesome to its authorities when it came to anti-regime efforts, as the Vasili Mitrokhin files from the KGB demonstrate.

There is hardly any mention of Poland in the book Christopher Andrew wrote about it, The Sword and The Shield, until the revival of Catholicism during the late 1970s under Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, and the rise of Lech Walesa’s Solidarity Movement in the 1980s.

Until then, the Polish regime had essentially bought off its opponents under the watchful eye of Moscow. When the fear of Soviet military intervention collapsed in Poland, the regime fell surprisingly quickly, like a stack of cards.

For anyone living in Europe after WWII, especially in the Soviet bloc, Poland offered the least insights into how to deal with Soviet Communism domestically, and how it would fare in the world.

Poland seemed like the worst place to choose as a jumping off spot for some kind of better future as the soft, repressive character of its communist regime appeared like a fixed monolith, quite impervious to change, because of the immediate presence of the USSR right next door – what turned out to be a paper tiger when Mikael Gorbachev took over.

Actually, a more flexible, compromising attitude towards an invader seems like a more profitable course for an subject country, as France experienced under Nazi rule, and after its liberation. Paris, always worried about the discontinuaties of its turbulent past, always kept a lifeline to its republican past, no matter how comforting the autocratic ways of Marshal Pétain, and the prospects of the Nazi invaders seemed while it too experienced partition with the creation of the Vichy regime.

The duplicity of all concerned was well-illustrated by the behavior of the National Assembly which voted away its power after the fall of France, only to try to restore itself after the departure of the Germans. The Marshal’s infamous Deputy Premier, Pierre Laval, and then his successor, Admiral Darlan, were quite prepared to work for the Nazis until it seemed much more profitable just to work for themselves.

Charles de Gaulle – The Statesman