By: Rima Najjar

If you are not a Palestinian and reading this, I have a little quiz for you to check on whether you can spot what jumped at me and may not jump at others.

The question is: Does anything strike you as odd about the immigrant groups that David Goodhart, ex-director of the British think tank Demos, enumerates below, as he presents his argument that the impact of “high levels of immigration” is detrimental to balanced global development?

“Immigrants contribute to [economic] innovation. We’ve got a great record of Jewish, East African, Asian and other groups creating great entrepreneurial initiatives, they fill skill gaps, they do dirty jobs…”

Anything? In particular, if you are Jewish, does anything odd strike you about the above?

What’s odd to me is the fact that the Jewish group in Goodhart’s list of immigrant groups above is not tethered to a geographic region as are the east African and Asian — and a little later in his speech, eastern European — groups he mentions.

Incidentally (or not), Goodhart himself is partly Jewish. At the beginning of his speech, by way of priming the audience to accept his thesis and show that he cannot possibly be biased, Goodhart attests to the fact that he has “two immigrant grandfathers, one Jewish.”

[Note: My own language is slipping — even as I am pointing out a slip! As a friend commented upon reading my post: “Partly Jewish? Jewishness is NOT divisible. Either one is or one is not and, either way, it has nothing to do with race or genetics.”]

The point Goodhart wishes to emphasize, of course, is that they are both immigrants, so it’s not important for the audience to know from which region of the world his immigrant grandfathers come. Nevertheless, he specifically identifies his Jewish grandfather, and that identity seems to have no particular “homeland” from which to immigrate to Britain.

Why is Goodhart speaking about immigrant Jews in this way? Is he a Zionist (consciously or unconsciously) identifying with a Jewish national right to national self-determination apart from the nations among whom Jews exist all over the world?

Would he have mentioned Israel, instead of using “Jewish,” had his grandfather emigrated from there to Britain? On second thought, this hypothetical doesn’t work, because, given Goodhart’s age, his grandfather would have emigrated from Palestine, not Israel, in such a scenario. If Goodhart himself identifies as Jewish, what does he think of the underbelly of Jewish immigration to Israel, past and present?

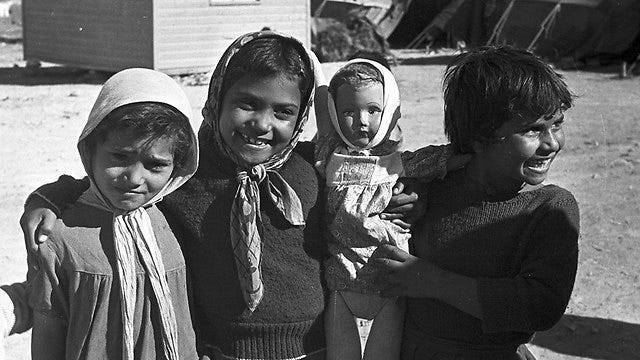

These questions forced themselves on my consciousness the minute Goodhart uttered the word “Jewish” in such a way. My family is Palestinian, displaced by war, forced to take refuge elsewhere — a kind of emigration by fire, with a twist. My family was denied return to our homeland, so that eastern European Jews could have Jewish national self-determination in Palestine and literally live in my grandfather’s house (that’s the twist).

When Goodhart says, “Of course many people that come here [meaning Britain] are complementary to existing workers. But there is obviously displacement too; there is clearly displacement at the bottom end,” I wonder if his worldview, which has, by his own account, shifted from left to right on immigration and multiculturalism, can encompass this upside-down reality of immigration in another part of the world.

I wonder because of his own reference to “an explicable worldview” that shapes our beliefs:

I referred to changing my mind as though it were a rational process, in which one audits one’s beliefs every few years and decides to shift ground on Israel/Palestine or the single market. But that’s not how it works. If, like most educated people, you place a high value on moral and intellectual coherence, your views tend to fit together into something like an explicable worldview.

Goodhart continues: “Newcomers [immigrants] can be absorbed into such [western democratic] societies, and can retain some of their own traditions, but unless a critical mass of them embrace the broad common norms of the society, the idea of the nation as a group of people with significant shared interests — the idea of a people — will fracture.”

The thought that leaps to my mind here is not about fracturing the idea of a people through immigration, but the manufacturing of such an idea, as the Zionist project has done with the idea of a “Jewish people.”

Immigrant Jews to Palestine fractured the people into whose homeland they immigrated. The settler-colonial state they established there and continue to maintain by force and brutality went on to prey on other Jews.

Four years ago to the day Israeli Minister Hanegbi admitted that “hundreds” of Yemeni infants had been stolen from their mothers, who were told their children had died, when in fact the infants were given to European Ashkenazi Jewish parents for adoption.

From 1948 to 1954, hundreds of newborn babies and toddlers of Arab and Balkan Jews in Israel began to disappear. They were the children of Yemenite and Mizrahi immigrants. More than 1 thousand families all report nearly identical stories…that they went to the hospital to either give birth or do a check-up on their children, and then their babies disappeared. At the time, state authorities claimed the babies had died and had already been buried, but until today, these families believe their children are still alive, and were either given or sold to Ashkenazi Jewish families- many of which were Holocaust survivors that couldn’t have children of their own.

Goodhart’s Jewishness, in as much as I can understand his phrasing above in describing immigrant groups, lumps all Jews in one “tribe,” and places them essentially in a floating “diaspora” in the world. “Jewish immigrants” are supposed to think of themselves as not coming from European countries of their birth, but from some mythical “Jewish people” that has led us tragically to the Nakba of Palestine. Goodhart’s phrasing is an underhanded and deeply harmful “meme,” so entrenched that perhaps only a few people pause, as I did, to question it.

Until 1965 there were two separate entries in the application to immigrate to the US: country of birth and race. Isolationism, xenophobia, antisemitism, racism, and economic insecurity played a role in US immigration policies between the two World Wars. For example, 110,000 Jewish refugees escaped to the United States from Nazi-occupied areas between 1933 and 1941 and hundreds of thousands more applied to immigrate and were unsuccessful. However, these Jews were all citizens and nationals of distinct European countries.

Immigrant Jews to Britain do come from somewhere in the world where they originally belong. Today, “Jewish immigrants” are never registered as “Jewish” in the US or elsewhere, but are registered according to where they were born and raised.

A friend explains that the idea of a “Jewish people” was not invented by Zionists but rather emerged from the anti-assimilationist ideas of generations of rabbis in Europe:

It is a thousand-years-long behavior of the Jewish rabbinical elite. When they noticed that Jews started to secularize and were likely to stray away and assimilate, they decided to create an ideology that would AGAIN separate Jews from Gentiles forever, based on “nationalism” that would propagandize secular Jews.

My point here is not that it is the Zionist project that invented the idea of a “Jewish people.” My point is that Zionism used this idea as a weapon that destroyed Palestine.

Zionist settler colonialism is built on coercive containment and expulsion and a manufactured idea of Jewish “peoplehood.” The sooner the world understands this, the sooner Palestinian liberation will arrive.